DEPARTMENT OF SPEECH, HEARING & PHONETIC SCIENCES UCL Division of Psychology & Language Sciences |

|

John Wells’s phonetic blogemail:

To see the phonetic symbols in the text, please ensure that you have installed a Unicode font that includes all the IPA symbols, for example Charis SIL (free download).

Browsers: Some older versions of Internet Explorer and Safari have bugs that prevent the proper display of certain phonetic symbols. I recommend Firefox (free) or, if you prefer, Opera (also free).

|

|

No blog entries for 14-15 May, because I was in Berlin to give two lectures.

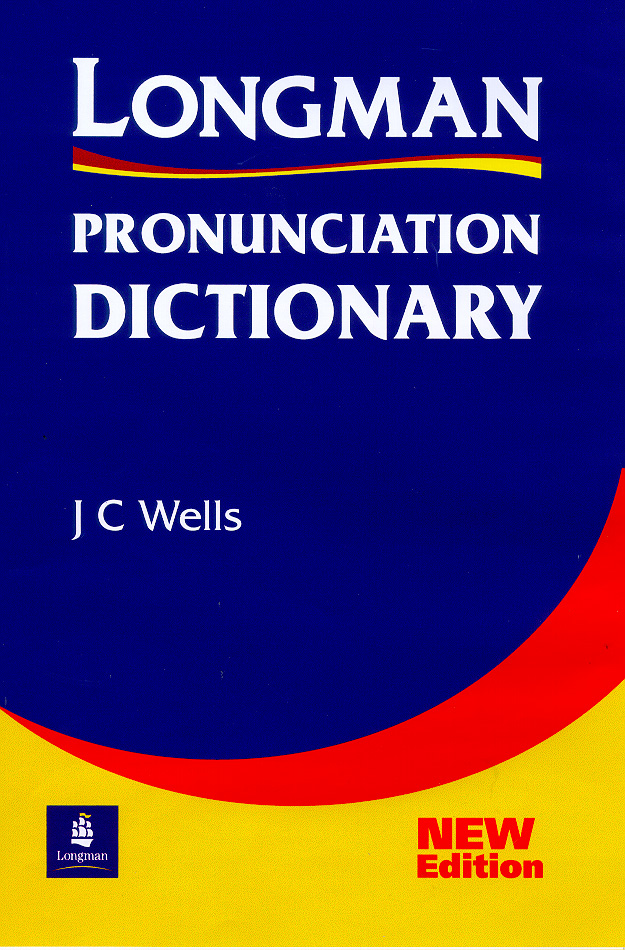

| Friday 11 May 2007 | Pronunciation preference survey 2007When I was compiling the first edition of the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, I thought it would be a good thing to get some survey data on the pronunciation of words where usage is divided. The sociolinguists tell us that people don’t report accurately on their actual usage; but there is no reason to suppose that they cannot accurately report their preferences in such matters. As a lexicographer, I thought that this would be a useful check on how accurate my own perceptions were. In 1988 I managed to recruit 275 respondents and was able to report on preferences in some ninety items such as zebra with /e/ or /iː/ and again with /e/ or /eɪ/. For the second edition, in 1998 I conducted another poll, this time with nearly 2000 responses. This yielded statistics for a further ninety or so words, including schedule, scone and scallop. Now we are working on a third edition of LPD, and the time has come for a new poll. Time has moved on, and a paper-based poll is no longer appropriate: this one will be done entirely on-line. So I’d like to ask for your help (if you fall into the relevant demographic). Please, if you are a native speaker of British English, go to this website and record your preferences. And please recruit your friends, your family, your students to join in. The more responses we get, the more reliable the results will be. |

|

| Thursday 10 May 2007 | HappY endingsIn the discussion of bandied and banded (blog, 24 April) I failed to mention a complicating factor: that there are people who have tense [i] for the word-final happY vowel, but change it to [ɪ] before inflectional [d] or [z]. Such speakers therefore have [i] in bandy, taxi, study, coffee but [ɪ] in bandied, taxis, studied, coffees. It follows that for them bandied can still be homophonous with banded, and taxis (cabs) with taxes, despite the [i] in the uninflected form. Gary Taylor, creator of Gary’s (Estuary) Homepage, is one such, and wrote to me to remind me of this possibility. Other speakers, though, do not do this, but keep [i] even before an inflectional suffix. I have never come across anyone who distinguished the plural from the possessive. Probably cities and city’s are homophonous for everyone. You can get the same change of [i] to [ɪ] before -ful and -ment, giving [i] in beauty, accompany but [ɪ] (or even [ə]) in beautiful, accompaniment. An even more interesting case is suffixes beginning with /l/: -ly and -less. I have [ɪ] in happy, angry, but often change it to [ə] in happily and virtually always in angrily. The derived schwa can then trigger syllabic consonant formation, so that readily is [ˈredl̩ɪ], with a laterally-released [d]. Similarly, I think many, perhaps most, people say funnily and penniless with [-nl̩-]. |

|

| Wednesday 9 May 2007 | Avoiding ʌ and feng shuiThe British seem to have a kind of unstated but deep feeling that foreign words shouldn’t contain /ʌ/. I’m not sure whether Americans and speakers of other non-British accents share this feeling. You can see the effect I am referring to in the name of the Indian province of Punjab. Older readers may remember Peter Sellars as an Indian doctor singing to the patient Sofia Loren I remember how with one jab ...correctly making the first syllable of Punjab rhyme with one /wʌn/ (though not correctly rendering the length of the vowel in the second syllable). But more often these days I hear people saying things like /ˌpʊnˈdʒɑːb/, pronouncing the first vowel not as /ʌ/ but as /ʊ/. Yet in Hindi, Urdu, and Punjabi/Panjabi the name of this province is Panjāb (in Hindi, phonetically [pɐ̃ndʒɑb]). The Hindi/Urdu vowel transliterated as short a (i.e. the first vowel in Panjāb) is regularly mapped onto English /ʌ/. Compare the word pandit, pronounced in Hindi as [pɐ̃ɳɖɪt̪] and in English as /ˈpʌndɪt/ (and usually spelt correspondingly as pundit). Hindi pakkā becomes British English pukka /ˈpʌkə/. But pundit and pukka are so well integrated that people don’t realize that they are of Hindi origin. Evidently we don’t feel them to be foreign in the way that Punjab is perceived to be. It’s the same with the name of the Welsh nationalist party Plaid Cymru. The word for Wales is [ˈkəmri] in Welsh and ought to be /ˈkʌmri/ in English. But English people persistently say /ˈkʊmri/. And now from Chinese along comes feng shui, Mandarin [1fʌŋ 3ʂuei]. Aficionados know the that the approved English pronunciation is not the */feŋ ʃuːi/ suggested by the Hanyu Pinyin spelling but rather /fʌŋ ʃweɪ/. Yet... foreign words don’t have /ʌ/. So we get people saying /fʊŋ ʃweɪ/. |

风水 |

| Tuesday 8 May 2007 | The letter jOver the weekend I attended the annual British Esperanto Congress, held this year in Letchworth Garden City. (Ebenezer Howard, the guiding spirit of garden cities and the founder of Letchworth Garden City, was a keen Esperanto speaker). It was good of the local member of parliament, Oliver Heald MP, to agree to be Honorary President of the congress and to attend the opening ceremony. Naturally the organizing committee invited him to address the gathering, and he was happy to oblige. As invited dignitaries often do in these circumstances, he chose to address us with a sentence or two in Esperanto before continuing in English. Lexically and grammatically, his Esperanto was perfect. Full marks for that. But unfortunately he had only a sketchy idea about how to pronounce it. In Esperanto spelling the letter j has the same value as in IPA, namely a palatal approximant. But Mr Heale didn’t know this, and instead gave it its English value, [dʒ]. It was unfortunate for him that one of the most frequent words is kaj, meaning ‘and’, pronounced [kai̯]. And that the plural ending is j, as in diskutoj ‘discussions’, pronounced [disˈkutoi̯]. Mr Heald pronounced them [kædʒ] and [dɪˈskutɒdʒ] respectively. I’m glad to say he still got a warm round of applause for his effort. But it’s a good thing it wasn’t a conference of Welsh speakers, with words like bwrw and ynys. |

|

| Monday 7 May 2007 | Placing the suprasegmental symbolsWhere should phonetic symbols for suprasegmental features (tone, stress etc.) go? As I said on Friday, I think that the best place for them is at the beginning of the syllable, before the symbols for the segments. In order to pronounce a syllable with the appropriate tone, you have to know what the tone is before you start. You can’t wait until you’ve finished making the vowels and consonants and then add the tone as an afterthought. Logically, the tone is the first thing you need to know about a syllable. Articulatorily, for the Chinese word for ‘hemp’, [ma] with a rising tone, you have to get low pitch in place right at the beginning, so that the [m] is low-pitched, ready to start the rise. Acoustically, the F0 in this word is lowest at the beginning of the initial nasal. You’re too late if you start to think about the tone only when you get to the vowel (Hanyu Pinyin) or when you reach the end of the syllable (Sinologist practice). The same applies to stress marking. You need to know whether a syllable is stressed before uttering it, not afterwards. That’s the justification for the IPA practice, revolutionary in its day, of placing the stress mark at the beginning of the stressed syllable, as against the traditional English practice, still found in some dictionaries, of placing it at the end. In my view the IPA’s Kiel change in tone notation was a misguided concession to the Africanist and Sinologist traditions. (They disagree with one another, anyhow. In the Africanist tradition, currently the only approved IPA alternative to Chao letters, we have to write [mǎ], LH, for a rising tone.) In my LPD transcriptions I shall continue to place tone marks at the beginning of the syllable. | 2ma má

|

| Friday 4 May 2007 | Where should tone marks go?Sticking with Chinese for the moment: one of the things in LPD that people knowing Chinese have commented on is the fact that in transcriptions of Chinese words I decided to place the tone mark at the beginning of the syllable in question, rather than over the vowel or at the end. The sinologist tradition is to use a trailing tone numeral, thus ma2 (‘hemp’, with tone 2, a rise). This is also how you input tones in the Chinese version of Word (the word processor). In printed Hanyu Pinyin, however, the tone mark, if used, goes over the vowel, thus má. But if I had wanted to include this word in LPD, I would have transcribed it as [2ma], with the tone number superscript and leading. So: is the best place for the tone mark trailing (at the end), central (in the middle, superscript), or leading (at the beginning)? My motivation in choosing to write tone marks as leading was for consistency with the placement of stress marks in stress languages. Likewise, I place the pitch accent marks for Japanese at the beginning, not the end, of the mora concerned. The IPA, too, used to place tone marks at the beginning, thus [ˊma]. The tone symbols were iconic, i.e. their shape suggested the relevant pitch movement. This was changed at the 1989 Kiel Convention to the current IPA rule, which is to place a conventional (sorry!), non-iconic, mark over the vowel, thus [mǎ], or to use an iconic Chao tone letter, presumably trailing, thus [ma˨˥]. (You probably won’t see the Chao letter correctly unless you’re using IE7.) Before, during, or after? More on Monday. | 麻 |

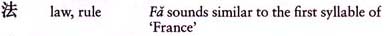

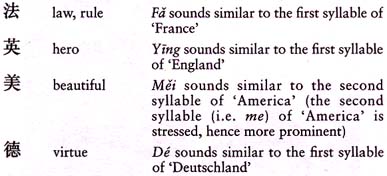

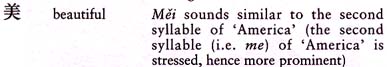

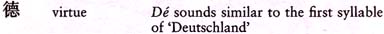

| Thursday 3 May 2007 | Chinese explanationsSeveral correspondents have hastened to point out that I had got hold of the wrong end of the stick when I wrote about the explanations given in Teach Yourself Beginner’s Chinese Script (yesterday’s blog). (NB. You’ll need to have a Chinese font installed to read everything that follows.) When the authors say

they don’t actually mean “the first syllable of France”. They mean that fǎ ‘law, rule’ is the same as (not “sounds similar to”) the first syllable of the Chinese word for ‘France’. The Chinese for ‘France’ is 法国 Fǎguó. So this name literally means ‘law country’. Similarly, the word for Britain, 英国 Yīngguó — rather charmingly — literally means ‘hero country’; the word for America, 美国 Měiguó, literally means ‘beautiful country’; and the word for Germany, 德国 Déguó, literally means ‘virtue country’. And all these names are phonetically reminiscent in some way of the European toponyms from which they are derived. So I am happy to withdraw my impugnment of the authors’ phonetic knowledge. But I still think they could have expressed themselves more clearly. And thanks to all those who wrote to me setting me straight.

| 法国 英国 美国 |

| Wednesday 2 May 2007 | How not to explain pronunciationHere is a scan of an excerpt from Teach Yourself Beginner’s Chinese Script by Elizabeth Scurfield and Song Lianyi (Hodder Education, 1999). The authors appear to be excellently qualified to write the book: Ms Scurfield got a First in Chinese at SOAS and is a former chair of the Department of Modern Languages at Westminster, while Dr Song is a Lecturer in Chinese at SOAS.

To be fair, this book is not mainly concerned with teaching the pronunciation of Chinese, but rather, as its title indicates, with teaching the writing system. Even so,...

Oh yes? With an /r/ between the initial consonant and the vowel? And how many syllables does France have, anyway? This word, furthermore, just happens to be a member of the BATH set, with a vowel sound that in Britain can be anywhere between [a] and [ɑː], and elsewhere — if we allow for the extremes of American and South African pronunciation — anywhere between [iə] and [ɒː]. What’s wrong with father as an example?

Why choose this particular word for exemplification? How are stress and prominence relevant? It would have been much simpler to say, accurately, that the Chinese word in question sounds very like the mainstream pronunciation of English may [meɪ].

Are you sure? Is the first syllable of Deutschland really an open syllable? Anyhow, what language are we talking about here? Certainly not German, where the vowel of this syllable is pronounced [ɔɪ] or [ɔʏ]. And not English, at least not for most speakers. When I was a teenager and studied Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poem The Wreck of the Deutschland, the English teacher pronounced the word with [ɔɪ], as does everybody I have ever heard say it in English. But Ms Scurfield must think it has [ɜː]. The Chinese pronunciation, by the way, is actually [tɤ], with a mid back unrounded vowel preceded by an unaspirated [t]. Many teachers think that phonetics is an unnecessary luxury for which there is no time in a busy language study schedule. But in this brief excerpt you see what the lack of elementary phonetics can lead to in material written by qualified authors and published by a reputable publisher. Not only is it factually wrong, it also fails to help the learner achieve the desired pronunciation. |

|

| Tuesday 1 May 2007 | Ylang-ylangOne word that I keep hearing (mis)pronounced on television is not a proper name, but a vocabulary word: ylang-ylang. This crops up not in the news but in a current commercial. The guilty party is the air freshener that I always thought was called Airwick but which is apparently properly written Air Wick. Air Wick, proclaims the voice-over, can fill your house with the delightful fragrance of /jəˌlæŋ jəˈlæŋ/. Oh dear. Dictionaries tell us that ylang-ylang, also written ilang-ilang, is a Malaysian and Filipino tree, Cananga odorata, with fragrant yellow flowers from which a perfume of the same name is distilled. The word comes from Tagalog, where it takes the form álang-ílang. (Just how this got converted into its modern English form is not clear.) Reference books are unanimous that this is to be pronounced /ˌiːlæŋ ˈiːlæŋ/ (or with final stress, and with the possibility of /ɑ/ rather than /æ/ in AmE). I think this error may come from children’s reading schemes in which the letter A is called [æ], B is [bə] and so on, so that the letter Y is called [jə]. And the voice-over person can never have read Chaucer, where words such as yclept might have helped. |

Archived from previous months:

my home page