DEPARTMENT OF SPEECH, HEARING & PHONETIC SCIENCES UCL Division of Psychology & Language Sciences |

|

John Wells’s phonetic blog — 1-15 October 2006email: To see the phonetic symbols in the text, please ensure that you have installed a Unicode font that includes all the IPA symbols, for example Charis SIL (free download).

|

|

| Friday 13 October 2006 | BBC TV is currently showing a rather well done series on Roman history, Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. As stated on the website, “The fourth part of this drama-documentary focuses on the story of the Jewish Revolt, which swept through Judea in AD 66, and a disgraced general's attempt to put it down”. What struck me was that every single actor pronounced Judea as /dʒuˈdeɪə/. But when I was doing Ancient History at school it was most definitely /dʒuˈdiːə/ (or rather the derived-by-smoothing /dʒuˈdɪə/). As far as I know, that’s still what people say in church, too. Judea or Judaea is the Latin name, via Greek Ἰουδαία, of the southern part of ancient Palestine. Two millenia ago, in those languages, it was pronounced something like [juːˈdaia] — but in both languages subsequently became [juːˈdeːa]. The regular development of this in English is /dʒuˈdiːə ~ dʒuˈdɪə/. Other names with a written e deriving from Latin ae and Greek αι include Egypt and Ethiopia. In English they still have /iː/. Other words with final stressed -ea include idea, diarrh(o)ea, Thea, and Korea. I have not heard /eɪ/ in any of them. For cases comparable to Judea, in which a traditional /iː/ now faces competition from an upstart /eɪ/, we have to look to nucleic and the -eity words: spontaneity, simultaneity, homogeneity, heterogeneity and above all deity. Indeed, for deity 80% of the BrE respondents in my 1988 pronunciation preference poll (reported in LPD) preferred the /eɪ/ form. Merriam-Webster gives both possibilities, while prioritizing /iː/ — as it also does for Judea, for which British dictionaries haven’t yet caught up with the possibility of /eɪ/. |

| ||||||

| Thursday 12 October 2006 | I am amazed at the wide readership this blog has achieved. No sooner had I expressed some scepticism yesterday about the eschew variant /eˈskjuː/ claimed by Merriam-Webster's Collegiate than the dictionary’s pronunciation editor, Joshua Guenter, emailed me. Here’s what he said. While I don’t claim to be any more certain than any other lexicographer, I can tell you that the pronunciation of “eschew” as /ɛ'skju:/ in our Collegiate Dictionary is based purely on citations. All of these citations are from the United States. We also have some citations for the pronunciation /ɛ'sju:/, but not enough to warrant its inclusion in any of our dictionaries. So I followed up by asking When you say "citations", does this refer to a spoken corpus? Or just to casual observations? (which, to be honest, are what I mainly rely on) &mdash to which Mr Guenter replied Something in-between. We have an enormous collection of data on 3x5 slips of paper. I don’t know how many of these we have, but it must be in the millions. They date back to the 19th century, though the ones dealing with pronunciation mostly started with Edward Artin in the 1940s. Most of the editors spend time “reading and marking” magazines, newspapers, etc., for data. The pronunciation editors write down examples of speech from TV, radio, speeches, conversation, etc. This is what we base everything in our dictionaries on. | eschew | ||||||

So there we have it: a very reassuring reliance on what we might term systematized casual observation. It confirms the opinion I had already formed: that in the absence of any more recent dedicated pronunciation dictionary for AmE than Kenyon & Knott (1953, now hopelessly outdated) the best source of information on word pronunciation in American English is the Merriam-Webster Collegiate. And it’s the only free on-line dictionary that offers you sound clips. |

| |||||||

| Wednesday 11 October 2006 | Apropos of eschew and the supposed unanimity of standard dictionaries (blog, 9 Oct), Kensuke Nanjo of St Andrew’s University (Momoyama Gakuin Daigaku) in Japan writes to point out that “the pronunciation /eˈʃuː/ is recorded as the first variant in Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition (2003). /ɪˈʃuː/ is the second. Since I checked this dictionary when I transcribed eschew, these pronunciations have also been recorded as the first and second American variants respectively in my forthcoming Taishukan's Genius English-Japanese Dictionary, Fourth Edition (G4).” You can confirm the truth of what he says by checking Webster’s Online. There are even audio clips of /eˈʃuː/ and /esˈtʃuː/. Webster’s goes on to mention a possible pronunciation /eˈskjuː/. I wonder what the evidence for this is. To be honest, it looks to me like an uncertain lexicographer covering every possible spelling pronunciation. Kensuke Nanjo is joint editor of the book Voicing in Japanese. |

| ||||||

| Tuesday 10 October 2006 | In English intonation there are certain types of word and phrase that tend not to receive the nucleus, even though they may be the last lexical item in an intonation phrase. They include various nouns that have very little meaning of their own, particularly vague general nouns such as things, people &mdash often known as ‘empty words’. I 'keep 'seeing things. 'What are you going to 'tell people? Tamikazu Date, having just read the section in my book English Intonation that deals with this point, mentions the greeting expression How are things?. “Where would the nucleus occur?” he asks. “Probably on the question word how? Yet don't some native speakers put the nucleus on the empty word things?” The problem is that the nucleus has to go \/somewhere, and if all the other words in the IP are function words then it will even go on a weak (‘empty’) content word. In fact, this is the usual tonicity for this question. 'How are \things? Actually, for reasons I cannot explain, people like me usually violate number concord here, and say 'How’s \things? — though that is not relevant to the intonation. (Google shows about half a million hits for How’s things, as against about two million for How are things.) A nucleus on how (Tami’s suggestion) would constitute marked tonicity, and could only be, for example, a disbelieving echo question.

|

| ||||||

| Monday 9 October 2006 | Michael Covarrubias of Purdue University writes: What surprises me is the unanimity with which descriptive dictionaries fail to report this common American form. Any time I have called attention to the standard pronunciation /ɪsˈtʃuː/ the claim is met with skepticism. At least in the midwest of the United States the affricate has become a pure fricative. I have wondered if this might be by perceived analogy with "shoo." The similarity is just enough for me to notice. I thank you for your attention to this minor issue (or is that ischue?).” Thanks for the observation, Michael. I’m not sure, though, that it is right to speak of the affricate having ‘become’ a fricative, as if this were an ordinary sound change. (This switch doesn’t apply to any other words, as far as I know.) Rather, /ɪsˈtʃuː ~ eˈʃuː/ is a lexicophonetic ‘alternation’ or ‘transfer’ (like controversy varying between initial-stressed ˈcontroversy and antepenultimate-stressed conˈtroversy), and its origins must, I think, lie in a spelling pronunciation in which speakers coming across the word first in writing interpret sch as having its German value of /ʃ/. Why they should do this, given that the spelling of the rest of the word shows that it is not German, and in the face of familiar English words like school and scheme with /sk/, is another question. The only common word that in BrE has /ʃ/ corresponding to sch is schedule; and this is a word which Americans, and now increasingly Brits, pronounce with /sk-/ anyhow. Michael’s idea of contamination from shoo doesn’t really seem very plausible to me, though it’s a nice thought. You can also read Michael’s own blog. |

| ||||||

| Saturday 7 October 2006 |

| |||||||

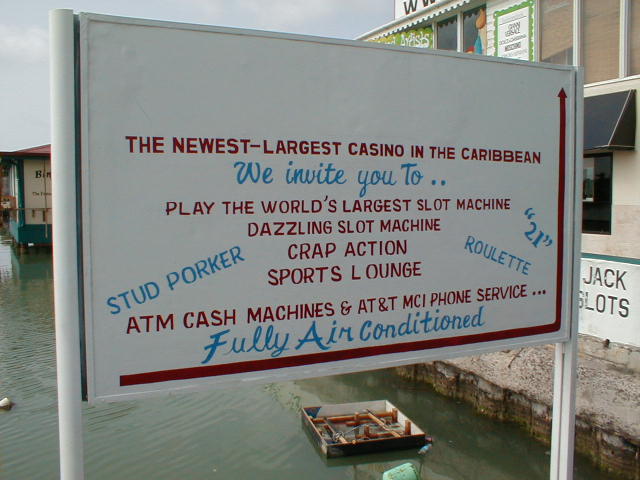

Fans of Language Log will have seen my photo (above) taken on the quayside at St John's, Antigua, where the cruise ships dock. It serves to attract the cruise passengers to various forms of gambling, including stud porker (sic). In the English of Antigua, as in that of the nearby Montserrat that I often visit, pork is a homophone of poke [poːk], which explains this spelling mistake. It is not a matter of “r-fulness on the march” or “a sneaky little creeping /r/”, as Roger Shuy presents it on Language Log. It is not a matter of sounds at all, just of spelling. Neither the Antiguans nor most English people have an /r/ in pork. The problem is not the sound /r/ but the letter r. Just as with larva and lava (blog, 6 September), we speakers of non-rhotic English may have difficulty in knowing which words to spell with r and which not. When we look at different accents of English, there are two sets of words spelt with -or-. In terms of the Standard Lexical Sets of chapter 2 of my Accents of English, some belong in the FORCE set and some in the NORTH set. It is the FORCE words that in Leeward Islands English fall in with the GOAT words, producing such homophones as court-coat, porch-poach and indeed pork-poke. The NORTH set, on the other hand, fall in with START in the local Creole, producing homophones such as form-farm, born-barn, lord-lard. North [naːt] and bath [baːt] rhyme. But pairs such as hoarse-horse are distinct, [hoːs] vs. [haːs]. Most Scots and Irish people preserve the distinction between the FORCE and NORTH sets. They, the Jamaicans and the Leeward Islanders are conservative in this aspect of their pronunciation. They retain a historical distinction that most of us have lost. | ||||||||

| Friday 6 October 2006 | I am reading Alan Bennett’s Untold Stories. It includes his diaries for 1996–2004, and for 11 August 2000 there is this entry: En route for Petersfield and A[lec] G[uinness]’s funeral I turn off the A3 to look at Ockham church and eat my sandwich lunch in the churchyard. It’s locked but a rather grand woman who’s working in the churchyard opens it up. It’s the church of William of Ockham and Ockham’s razor (in Latin) is inscribed on mugs for sale at the bookstall. Coming out, I thank the woman and she says I’m lucky because she wouldn’t normally be around but they’ve been having trouble with the myrrh. The church hadn’t seemed to be particularly ritualistic so this puzzles me. The connected-speech processes that make RP mower a possible homophone of myrrh are those that I call Smoothing and Compression. Smoothing means the loss of the second element of a diphthong before another vowel, so that [ˈməʊ.ə] becomes [ˈmə.ə]. Compresssion reduces two syllables to one, producing a long schwa which makes the word sound identical to myrrh [mɜː]. Alan Bennett sees this as an upper-class pronunciation habit (‘a rather grand woman’), which is the same reaction as I tend to get from my native-English-speaking students when I tell them about smoothing: they think it belongs to ‘U-RP’. But I often use this reduction myself, and I am not upper-class — at best, I suppose I could be called upper-middle. |

| ||||||

| Thursday 5 October 2006 | Sometimes in reading we come across an unfamiliar word, a word that we have never heard pronounced. Native speakers and foreign learners alike, we may be tempted — rather than looking it up in a dictionary — not only to infer its meaning from the context but also to infer its pronunciation. But English spelling, as we all know, is not necessarily a sufficient guide to pronunciation, and we risk making a fool of ourselves. A few days ago I heard a BBC announcer say that someone /ɪˈʃuːd/ violence. This was not a mishearing or mis-stressing of issued, but meant to be the rather rare word eschewed. Those familiar with the word eschew pronounce it /ɪsˈtʃuː/ (or /es-/). All published dictionaries agree that that’s the way it’s said. The announcer ought to have sought advice. But perhaps she didn’t have the script in advance, and had to make an instantaneous guess. Unfortunately she got it wrong. Then yesterday I heard the Classic FM newsreader refer to /ˌjuːkəˈraɪətɪk/ organisms. He meant eukaryotic. This word is not in EPD or LPD (though LPD has the noun eukaryote). But I’m pretty sure most people who know the word pronounce it /ˌjuːˌkæriˈɒtɪk/. That’s what \/I do, | \anyhow. ‖ I’ll make sure it’s in the next edition of LPD. |

| ||||||

| Wednesday 4 October 2006 | Further to what I wrote yesterday about giving a lecture on exotic sounds: what is the best way to demonstrate the sounds one talks about? The lecturer can (i) demonstrate each sound personally, or (ii) call on native speakers of the languages in question to demonstrate them, or (iii) use recorded examples. A good lecturer probably uses all three methods, though different lecturers will use them in different proportions. I have always mostly used method (i), perhaps because I enjoy showing off a bit. I certainly believe that a competent phonetician ought to be able not only to describe and analyse the various sound-types but also to perform them. I find it very dismaying whenever one of my lab-bound or theory-bound colleagues refuses to actually perform the sounds they talk about. Method (i) also has the advantage of needing no special preparation (beyond the phonetic ability the lecturer should always be able to call upon). Method (ii) is excellent if you can get hold of suitable native speakers. In Poznań I had no friendly Zulu helper; but that also means that there was no one there who might claim that my own attempts at that language were inaccurate. In the event, the only sound for which I used method (ii) was the Swedish [ɧ], which was just as well because the Swedish lady who performed it for us felt that my own attempt at it was not precisely native-like (she told me privately). However I was confident enough to perform the Polish nasalized diphthongs myself, and doing this acceptably no doubt raised my credibility with the predominantly Polish audience. Method (iii) requires a lot of work finding and recording an appropriate native speaker — unless you can lay your hands on a ready-made sound clip or video clip. And in my experience such recordings don’t always work properly first time when embedded in Powerpoint. Nothing interrupts the flow of a lecture more than having to stop and fiddle with the technical equipment. |

| ||||||

| Tuesday 3 October 2006 | In the course of my stay in Poznań, as well as teaching the postgraduate students, I also gave a public lecture on the topic ‘The wonderful world of sounds’, or in Polish Cudowny świat dźwięków. This was a shameless canter through exotic sound-types. I had great fun demonstrating ejectives, implosives and clicks. Among my examples were the Zulu words for ‘shoe’ isicathulo [ísik͡ǀaˈtʰúːlo] (also the name of a dance — see pic), and ‘hat’ isigqoko [isíˈg͡ǃoːko]. I also pointed out that various sound-types found in familiar European languages are actually rather rare among languages of the world and therefore — from the point of view of much of mankind — exotic: the front rounded vowels [y, ø] of French, German, and neighbouring languages; the nasalized vowels [œ̃, ɔ̃, ɛ̃, ɑ̃] of French (un bon vin blanc), and the nasalized diphthongs [ẽw̃, ɔ̃w̃] (język, są) of Polish; the Swedish sj sound [ɧ], a voiceless fricative that no one quite knows how to classify in terms of place of articulation (?labial-postalveolar-velar); and not least the dental fricatives [θ, ð] (thick, this) and stressable long schwa [ɜː] (nurse) of English. The American [ɚ], a rhotacized mid central vowel, is found in very very few of the world’s languages. It just happens that two languages in which it is found are very widely spoken: American English and Mandarin Chinese. | |||||||

Archived from previous months:

my home page