DEPARTMENT OF SPEECH, HEARING & PHONETIC SCIENCES UCL Division of Psychology & Language Sciences |

|

My phonetic blog — August 2006John Wellsemail: To see the phonetic symbols in the text, please ensure that you have installed a Unicode font that includes all the IPA symbols, for example Charis SIL (free download).

Fund raising: please visit this page. |

|

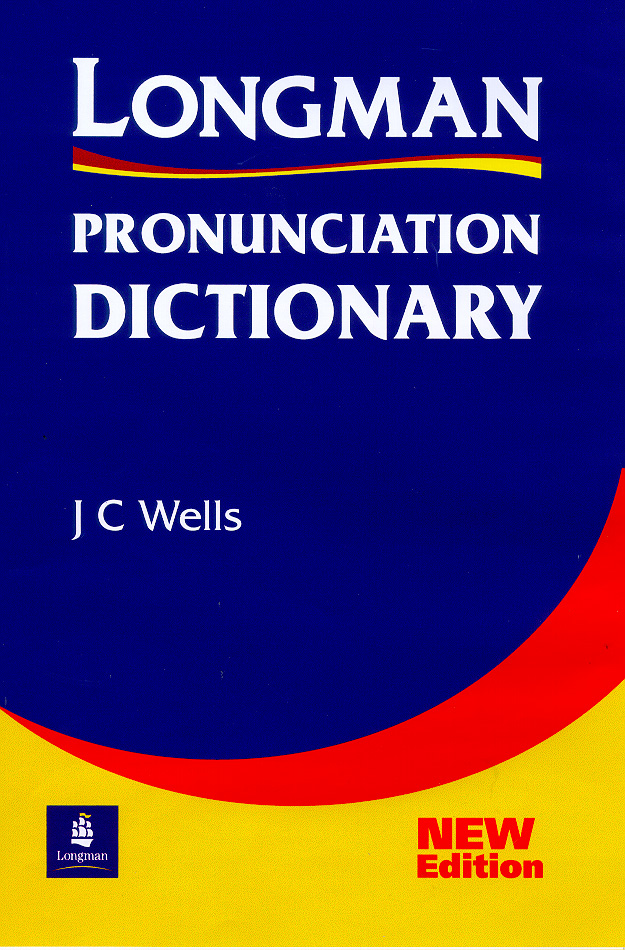

| Thursday 31 August 2006 | Today, according to amazon.co.uk, is the UK publication date for my new book English Intonation: an Introduction. (The publishers are a bit vague about the exact date.) After my experiences with the cows last week, I thought it would be worthwhile trying to attract some media attention to the book. So I drafted a press release for CUP to issue. Their reponse, however, was “regrettably we don't use press releases for this kind of book; it is only in our trade publishing that we use this method”. No press release. So here is part of what I would have said in the press release if one had been issued.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wednesday 30 August 2006 | Masaki Taniguchi, of Kōchi University in Japan, tells me he has been noticing odd things about floor numbers in London. The synthesized voice in the lift in the new hospital next to UCL sounded to him as if it were saying fast floor, though obviously the message was meant to be first floor. He wonders whether a human voice, too, might produce something intermediate between [ɑː] and [ɜː]. The answer is presumably yes, though all kinds of British English maintain a phonemic distinction between these two vowels. No native speaker has fast and first as homophones (though this vowel contrast is a well-known difficulty for Japanese learners). There are Americans (northern Ohio and elsewhere?) who sometimes seem to pronounce [ɝː] instead of [ɑɚ] in words such as start, but that is a different matter. So is the aborted historical development that has left us doublets such as person/parson and variability in the pronunciation of clerk, Derby. Then, in Waterstone’s bookshop, Masaki started asking people — Labov-style — where the linguistics books were. He thinks one assistant answered Thirst floor, which, if Masaki was correct in what he heard, is a nice example of hypercorrection, since they are actually on the first floor. TH Fronting, i.e. using [f] for [θ], is a well-known Londonism. For some working-class Londoners thirst and first are homophones, both [fɜːst]. (Hence the puns about thirst class, thirst rate.) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tuesday 29 August 2006 | For an opportunity to hear how one of the younger members of the royal family talks, go to this video clip of Zara Phillips, daughter of Princess Anne and thus granddaughter of the Queen. Like her mother, whom journalists once caricatured as Princess Unne, she uses a very open, retracted-cardinal-four kind of /æ/. The replacement of word-final [t] by sound-types other than a voiceless alveolar plosive proceeds apace. Zara uses an American-style voiced tap in ge[t̬] on, right at the beginning of the clip. In the expression I had a time fault she appears to have entirely omitted the final /t/. Otherwise, for post-sonorant word-final /t/ she uses a glottal stop, as with i[ʔ], bu[ʔ] he, wen[ʔ] ou[ʔ] today, capable of i[ʔ]. In this she is probably representative of people of her age and class (though not of people of my age and class, and sharply different from her grandmother). When she says No her lips are unrounded throughout. There are surprises in her grammar. Twice she uses the adjective fantastic in place of the adverb fantastically: he jumped fantastic, he was jumping fantastic. Any ordinary mortal who did that would be condemned as uneducated or recruited for Jenny Cheshire’s study of English non-standard grammar. And she says yeah instead of yes, which Judge Judy never allows a witness to get away with. It is fascinating to be able to observe the really rather substantial change of accent within three generations of one family as we proceed from mother to daughter to granddaughter. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monday 28 August 2006 | Another question from Xiangyan Sun: “/s, z/ may assimilate to a following /j/, but this seems very volatile. According to LPD, the word issue, for example, can be pronounced as [ˈɪʃuː] or [ˈɪsjuː] but not [ˈɪʃjuː], so it is with many others. By contrast, tissue has [ˈtɪʃuː], [ˈtɪsjuː] AND [ˈtɪʃjuː] (in order of popularity) but there seem to be relatively few such examples. How come /j/ is not always present after assimilation?” In English phonetics we traditionally distinguish between dealveolar assimilation, in which an alveolar consonant acquires a feature from a following consonant which itself remains unchanged, and coalescent assimilation, in which two adjacent consonants combine into a single consonant that includes features of both. So examples of dealveolar assimilation would be te[m] minutes, goo[ɡ] cook, ba[b] man, etc., and also thi[ʃ] year, the[ʒ]e units (where year, units retain their initial [j]). Some speakers, myself included, do not do dealveolar assimilation before [j]. Where the triggering [j]-word is you or your, the [j] usually disappears, so that unless you, as your become [ənleʃu, æʒɔː]. This is coalescent assimilation. More familiar examples of coalescent assimilation involve the creation of an affricate in what you, did you [wɒʧu, dɪʤu]. But all of the preceding applies across word boundaries. Within a word, coalescent assimilation involving /s/ or /z/ is not a productive process for most British speakers (although we have it as a historical legacy in words such as pressure, closure). Only a small minority pronounce assume as /əˈʃuːm/; most people say /əˈsjuːm/ or /əˈsuːm/. For nauseous we say /ˈnɔːsiəs ~ ˈnɔːsjəs/ (although Americans typically say /ˈnɔːʃəs/). |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the case of issue and tissue we are dealing not with a productive process but with alternative pronunciations. For me, they have always been /ˈɪʃuː, ˈtɪʃuː/, and I would consider these the underlying forms, not derived from some underlying */-sj-/ sequence. However, there are others who say /ˈɪsjuː, ˈtɪsjuː/ or /ˈɪʃjuː, ˈtɪʃjuː/. In my preference poll I found that 49% of my British sample said they preferred /ˈɪʃuː/, 30% /ˈɪsjuː/ and 21% /ˈɪʃjuː/. The younger the respondent, the more likely to prefer a form with /ʃ/. (I do not understand the comment about LPD: all three possibilities are listed against both issue and tissue.) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saturday 26 August 2006 | Apropos of the BBC commentators and the Chinese name Zhu (blog, 21 August), Anthony Bladon writes, “You can hardly blame them. They are probably generalizing zh as a fricative familiar from Slavic transliterations (Brezhnev). Also, I haven’t met any Zhu’s in the US who volunteer the affricate pronunciation for their name. Perhaps they just don't want to be called Mr. Jew...” Point taken. But no one seems to worry about other surnames that happen to correspond with ethnonyms: Scot(t), Welsh/Walsh/Welch, Irish, French, English, Flem(m)ing, German/Jermyn/Jarman, Dane, Finn, Lett(s). I know several black people called White, and several white people called Black or Brown. I also know people of non-Jewish parentage called Jewson. (And there is also a Chinese surname Goy 倪, anyhow.) There’s an interesting article on Chinese surnames in Wikipedia. Did you known that the same surname 吴/吳 can be romanized either as Wu or as Ng? or that 郑/鄭 Zheng can also appear as Teh, Tay, Tee, Zeng, Chang, Cheng and Chung? | 朱 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Friday 25 August 2006 | The cows-with-a-local-accent story is dying down now, I’m glad to say. My last telephone interview, yesterday afternoon, was with a radio station in Cape Town, and we were able to have quite a sensible conversation since the interviewer was a keen bird-watcher and knowledgeable about geographical variation in bird song. As far as cattle were concerned, I said I thought they were no more likely in Somerset to moo with a West country accent than they were in South Africa to moo in Xhosa or Zulu. The interviewer congratulated me on my pronunciation of Xhosa [ˈk͡ǁʰɔːsa] and went on to talk about the Hluhluwe Game Reserve: so I congratulated him in turn on his pronunciation of Hluhluwe [ɬuˈɬuːwe]. What fun to be a phonetician! If you can read German, you might like to see a good account of the whole non-story. The headline Dialektaler Rinderwahn means ‘dialectal mad cow disease’. The neat German equivalent of the silly season (Americans may not be familiar with this British expression) is the Sommerloch, ‘summer hole’. There’s also more on Language Log. Scroll down to OH, THE MOOS YOU CAN MOO and WHERE ARE MOO FROM?. On another matter, Daniel C. Hall of the University of Toronto writes to say that his browser, iCab version 3.0.3 running on Mac OS X version 10.4.7, renders the contour tones (blog, 23 August) correctly. Nice to hear that at least one browser does so, even if it’s still in beta and available only to Mac users. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thursday 24 August 2006 | It’s the silly season — August, when there is not much political news, so the newspapers print stories that are not altogether serious. I was telephoned by a public relations consultant on behalf of a cheese manufacturing company in Somerset. Was it possible, they asked, that the local cows might moo with a west-of-England accent? I told them that I thought it was highly unlikely, but that there had been serious research showing that various species of bird exhibit geographical variation in their calls. And if birds and human beings have local accents, you can’t entirely rule out that cows might too. The PR company issued a press release. They showed it to me only after they had sent it out, which meant that it was too late for me to protest that they had put into my mouth the solecism “This phenomena is...”. Of course I would always say only “This phenomenon is...” or “These phenomena are”. The press release was embargoed until midnight. At half past midnight yesterday my phone rang: it was a call from BBC Radio Five Live setting up a telephone interview for 00:55. After I’d done that, I snatched a few hours sleep, but was woken by a call from Australia, about bovine dialects, at about 05:45. From then on my phone hardly stopped ringing all morning. In all yesterday I did fourteen phone interviews plus three television interviews, one of them transmitted live from Vauxhall City Farm in central London in the rain, alongside a disconsolate heifer. We couldn’t get it to utter any kind of moo. You can read on-line reports from the BBC, ITV, the Guardian, and The Register. There are even articles in Polish, German and Hebrew. I shall be invoicing the PR company for a full day’s work. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wednesday 23 August 2006 | One of the two currently IPA-approved ways of showing tone in tone languages is by the use of the tone letters devised by Yuen-ren Chao (Chao , Y.R., 1930. A System of Tone Letters. m.f. (Le maître phonétique) 45:24-27). As shown in the IPA chart, they consist of an iconic line attached to the left of a vertical stem. (The relevant part of the Chart is reproduced on the right.) How can web authors encode these tone letters? The five level tones are catered for at U+02E5..9 in the Spacing Modifier Letters block. They are available in the phonetic fonts we use. Provided you have a phonetic font installed, you should see them here: ˥ ˦ ˧ ˨ ˩. But what about the contour tones? They are not directly provided for in Unicode. Potentially, there are a rather large number of contour tone letters. With five pitch levels for the starting point, multiplied by four different pitch levels for the end point, we have 20 symbols for simple falls and rises. For rise-falls and fall-rises we need another 20, and for other complex contours still more. What we have to do, I am told, is to encode contour tones as sequences of level tone letters. Then if your web document contains a string of two or more tone letters with no intervening spaces the rendering software in your browser ought to convert into the corresponding contour tone letter. So the ‘Rising-falling’ letter on the Chart would be encoded ˦˥˦. The browser you are using renders this as ˦˥˦. As you can see, current browsers don’t know about rendering contour letters. Maybe the next generation will. (Thanks to Peter Constable for this information.) Intuitively, however, I find that I would prefer to have the stem on the left. Clearly, I am not alone in this. Version 4.1 of the Unicode standard adds left-stem tone letters, encoding them as U+A712..6. This revision came too late for the current SIL Charis and Doulos fonts, which do however include them in the Private Use Area at F1D0..4. So you may be able to see them on your screen here: . |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tuesday 22 August 2006 | A current UCL MA Phonetics student, Xiangyan Sun, has sent me a sound file, a brief extract from the weather forecast. The relevant part goes ...it will be a pretty miserable weekend... (I think I am right in hearing it will be rather than it would be, which is what Xiangyan thought the speaker said.) His question relates to the word miserable, which here he wants to transcribe [ˈmɪʒəbl]. He asks, “Does the /r/ cause /z/ to assimilate to [ʒ] (regressive de-alveolar assimilation) and then get omitted, or do /r/ and /z/ coalesce into [ʒ]? And in theory, can /r/ be omitted after /ʒ/?” My answer was to congratulate him on his observation and on the query he raises. I think what we have is as follows.

But others may disagree.

If this is a productive process, we could predict that rhinoceros /raɪˈnɒsərəs/ might sometimes be pronounced [raɪˈnɒʃʊs]. That doesn’t seem awfully plausible, so perhaps [ˈmɪʒʊbl] is a one-off.

One of the Chinese competitors in the athletics championships in Birmingham on Saturday had the name Zhu. BBC sports commentators, despite the efforts of the BBC Pronunciation Unit, continue to get this and other Chinese names wrong. Sometimes they said /ʒuː/, sometimes /zuː/, but never the correct anglicization /dʒuː/.

In Pinyin, the official romanization of Modern Standard Chinese (Mandarin) in the People’s Republic, zh stands for an unaspirated post-alveolar affricate. The post-alveolar series ch, zh, sh, r are respectively an aspirated affricate, an unaspirated affricate, a voiceless fricative and a voiced fricative. Chinese also has a series of alveolo-palatals: affricates q, j and fricative x.

Obviously the romanizations zh, q, x are particularly deceptive for speakers English (and of many other languages). But you just need to learn them. Cut out and keep this list of English equivalents.

In Taiwan the Wade-Giles romanization is still in use. The name written Zhang in Pinyin is the same as the one written Chang in Wade-Giles. Pinyin Zhao is Wade-Giles Chao. And Pinyin Zhu is Wade-Giles Chu. (Conversion tables)

It would be unreasonable to expect English sports commentators to master the distinction between post-alveolar (retroflex) and alveolo-palatal (which is arguably allophonic, anyhow). But phoneticians will want to: so here is a table for us. All the obstruents are voiceless. The fortis series are aspirated, the devoiced lenis series unaspirated.

You can hear sound files of all possible Pinyin syllables, with tones.

The planets have been in the news recently, as astronomers try to define just what a planet is and exactly which heavenly bodies qualify. One of the candidates for planetary status is Charon, Pluto’s moon.

How do we pronounce Charon? Wednesday evening’s ITV news had it as /ˈʃeərən/. I didn’t hear how the BBC reported it: let’s hope their newsreaders are more enlightened.

Charon is traditionally pronounced in English with /k/, just as are other Greek words and names spelt ch-: Charybdis, chemistry, chiasmus, chiropractic, chlamydia, Chloë, chlorine, chlorophyll, cholesterol, choreography, Christ, chromosome, chronograph, and also (usually) chimera, chiropody.

Pronunciation dictionaries are unanimous for initial /k/ in Charon: /ˈkeərən, ‑ɒn/.

Long before his name was given to the moon of Pluto, Charon was a figure in classical mythology: the grim ferryman who ferried dead souls across the river Acheron (or Styx) in Hades.

I well remember Charon from Virgil’s Aeneid, book six, line 299. As a teenager I was required to learn off by heart 20-30 lines of it:

Virgil’s hexameters make it clear that the first vowel in Charon was actually short in Greek and Latin:

The Greek form, Χάρων, makes it clear that his second vowel was long.

So perhaps we ought to be saying /ˈkærən/ (or even /ˈkærəʊn/) rather than /ˈkeərən/.

I found most of the Latin literature I studied at school and university pretty uninspiring. But the sixth book of the Aeneid was an exception. Virgil’s lines about the lost souls yearning to be transported across the river really have that tingle factor:

To this place there rushed a whole crowd, pouring out onto the river bank: mothers and men and the lifeless bodies of great-hearted heroes, boys and unwed girls, young men placed on the funeral pyre before their parents: as many as the leaves that fall in the woods at the first frost of autumn, as many as the birds that flock together on the land, leaving the deep abyss, when the cold weather drives them across the sea to warmer lands. They were standing there, praying to be carried across first, and holding out their hands in yearning for the opposite shore.

Anne Fabricius of Copenhagen has set up a Modern RP page. She writes, “My aim in making ‘The Modern RP page’ is to create a site which will gather teaching resources on the internet and references to published works in books and journals, and be a forum for my own research thinking to develop.”

Rod Walters writes from South Wales that he has now made available on his website documents and recordings relating to Rhondda Valleys English, the topic of his PhD dissertation. There are extensive sound archives and transcripts.

Paul Nulty, who read my blog entry of last Friday, writes “I live near Ranelagh in Dublin. By far the most common local pronunciation is the BBC Pronunciation Dictionary way, rænlə. There are some small variations but I've never heard the other way (ranleigh/rænlee) in Dublin.

The Irish pronunciation you gave is pretty close but I would leave silent the voiced velar fricative [gh] and palatalise the n in "Raghnallach" — but my IPA is a bit rusty so maybe I’m not sure. If you’re ever in Dublin you can get the tram out there and hear for yourself the electronic voice pronouncing it in Irish on the tram!”

As I breasted the brow of a rather steep hill during my running club’s Sunday morning social run last weekend, a fellow runner sweetly enquired,

Did you run up that hill?

My answer was

\No, | I’m a'fraid I \didn’t. ∥ I 'have to admit I \walked up.

However what interests me here is the intonation used by my interlocutor. She had a wide falling pitch on run and then a wide rising pitch on hill. The problem is to decide whether she was using (a) a fall tone followed by a rise tone, or (b) a fall-rise tone:

(a) Did you \run up | that /hill?

(b) Did you \/run up that hill?

I think the answer is (b), for three reasons.

First, we both knew we’d just got to the top of a hill. So from the pragmatics of the situation, that hill was old information (given). Accordingly, we would not expect focus on those words: we would not expect them to be accented. Analysis (a) places not just an accent but a nuclear accent on hill; analysis (b) treats it as unaccented.

If, introspecting, I change the tone on run into a rise, but otherwise keep the pragmatics the same, I find myself saying not (a′) but (b′):

(a′) Did you /run up | that /hill?

(b′) Did you /run up that hill?

And if I had not heard clearly and had asked her to repeat the question, I think she would have then said not (a″) but (b″):

(a″) Did you \run up | that \hill?

(b″) Did you \run up that hill?

Thirdly, if — introspecting again — I ask myself how she would have said the same thing without the last three words, but keeping the pragmatics the same, I feel pretty sure she would have said not (a‴) but (b‴):

(a‴) Did you \run?

(b‴) Did you \/run?

Conclusion: she used a single intonation phrase, with a fall-rise tone on run.

I think that phoneticians, or at least intonologists, have to be ready to perform mental speculations like this to elucidate structures, just as syntacticians do.

A fall-rise tone on a yes-no question is heard increasingly frequently.

Which language makes use of the schwa symbol in its everyday orthography?

There may be various such languages only relatively recently reduced to writing by missionaries or linguists. It is difficult to find information about how many they might be, or what they are called. I do know that it is used in the Latin Chechen alphabet, though this language is more usually written in Cyrillic.

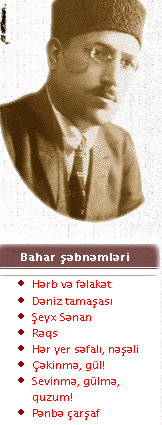

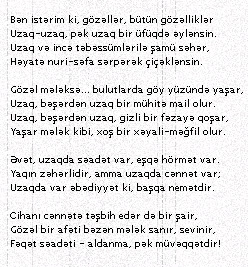

However, there is one well-established language, spoken by tens of millions of people, that uses the schwa symbol: namely the Turkic language of Azerbaijan, Azeri, also known as (North) Azerbaijani. Alongside you see screenshots of an Azeri website devoted to the poet Hüseyn Cavid, with orthographic schwas prominently in use. You can see plenty more if you go to the Azərbaycan version of Wikipedia, Vikipediya.

The schwa letter comes in upper-case as well as lower-case, as you can see at the beginning of line 9 of the sonnet.

However, the sound denoted by Ə, ə is not the IPA’s mid central vowel but a front open vowel, [æ].

Strangely, Unicode includes three identical-looking versions of the schwa symbol. One is, as expected, in the IPA Extensions block at U+0259. Another is in the Cyrillic block, at U+04D9, with an upper-case version at U+04D8 — this is fair enough, given that schwa is also a Cyrillic letter, used when writing Azeri (and some other languages) in Cyrillic. The third, however, is at U+01DD, and belongs to the Pan-Nigerian alphabet; it is called ‘turned e’ and is distinguished from the ordinary schwa inasmuch as it has a different upper-case form (Ǝ if your font includes it). This is also used in the transliteration of Avestan. “All other usages of schwa are 0259 ə”, says the Unicode standard; and this has a similar but larger upper-case form, U+018F Ə. That is how the Azeri schwas are encoded.

The Azeri word for ‘and’ is və. Doing a Google search on this word produces 1,820,000 hits if we encode the vowel as U+0259, but only 654 if we write it as U+01DD.

Although the current official orthography in Azerbaijan is Latin-based, it was Cyrillic during Soviet times and before that Arabic.

There are also millions of Azeris living in Iran, but their Southern Azerbaijani, we read, has its own distinctive phonology, lexicon, morphology, syntax, and loanwords. They mostly use Arabic script.

One day recently the London Underground line that I normally use to travel to work was suspended because of a signal failure, and would-be passengers were advised to use bus services instead.

As I duly sat on the bus I overheard a fellow passenger making a call on his mobile.

I’m on a \/bus, | cos the \Northern Line is screwed.

What is interesting here is the tonicity of the second intonation phrase. Why does the nucleus go on Northern? At first glance you’d expect it to go on screwed (= out of order), which is new information.

This is an instance of a sub-category of ‘event sentences’, namely those that report disasters. In these the nucleus is placed on the subject noun rather than on the verb (etc.). Compare

The roof has collapsed.

I’ve just heard that my father’s dead.

That would account for

The Underground’s screwed.

Since everyone knows that the London Underground consists of various named Lines, the word Line itself is predictable, and we have a lexicalized contrastive stress pattern for each Line: the ˈCircle Line, the ˌBakerˈloo Line, the ˈNorthern Line. Hence

the Northern Line is screwed.

Nor

I discuss event sentences in section 3.30 of my forthcoming English Intonation: an Introduction. By the way, Cambridge University Press tells me that the UK publication date is now set for 31 August — too late, unfortunately, for me to be able to autograph copies for our summer course participants.

On Thursday evening we held the staff dinner for the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics, and as usual I had to give an after-dinner speech. Here I am in mid-flow. The other people in the picture are all phoneticians, tutors on the course: left to right, Jane Setter, Patricia Ashby, Jill Ramsey, Jack Windsor Lewis, and Brian Mott. The photographer was Michael Ashby, who next year will take over the running of the course.

I’m a member of a running club, Wimbledon Windmilers. Sometimes we participate in events where other clubs are also involved, and one of our neighbouring clubs is Ranelagh Harriers. How do you pronounce Ranelagh?

According to the BBC Pronouncing Dictionary, it’s /ˈrænɪlə/. But last week I observed carefully how the spectators at an event where they were running cheered them on. They shouted “Come on /ˈræn(ə)li/!”.

Fortunately I’ve got both prons in LPD. (That’s perhaps because I remember my mother using the /‑i/ form.) Do you think I ought to change the prioritization, to put /ˈrænəli/ first? Is there anyone with first-hand knowledge of this name? There are several streets in London called Ranelagh Avenue, Ranelagh Place, Ranelagh Gardens etc.

The name looks as if it is of Irish origin, being an area of Dublin. In Irish it is Raghnallach, presumably [ˈraɣnəɫ̪əx] or the like. Ranelagh Gardens in London, according to Wikipedia, has variant spellings Ranelegh and Ranleigh, which might explain the /‑i/ pron. They were named after the Earl of Ranelagh, treasurer of Chelsea Hospital 1685-1702. “The title Earl of Ranelagh was created in the Peerage of Ireland for Richard Jones, 3rd Viscount Ranelagh.” It is now extinct.

The visiting lecturer at the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics yesterday afternoon was a former UCL MA Phonetics student, Martha Figueroa-Clark. She is now employed by the BBC, as one of the three researchers who staff the BBC Pronunciation Unit. Her lecture, interesting and informative, was about its work.

The Unit reacts to queries from newsreaders and presenters and also prepares daily and weekly lists for them of names in the news. Mostly these concern names from various foreign languages — the Unit does not presume to lay down the law about how to pronounce English, but rather to give helpful advice about foreign names. It certainly doesn’t prescribe the use of RP or any other particular way of pronouncing English, nor does it insist on particular pronunciations such as ˈcontroversy vs. conˈtroversy or /ʃ/edule vs. /sk/edule.

The BBC uses a special respelling system rather than IPA, since it is intended for native speakers of English (not phoneticians) addressing other native speakers of English.

The Unit staff post regular blog entries on the BBC website. As of today, the three most recent are all written by Martha.

If you’d like to read what the BBC itself has to say about the Unit, see this report of a visit by my friend Tim Gossling, with explanations from Martha’s colleague Catherine Sangster.

Bryan Parry, a student at the University of Westminster, takes me to task for using what he sees as inaccurate phonemic symbols for English.

“My /ʌ/,” he claims, very reasonably, “seems to be far closer to [ɐ] than to (cardinal) [ʌ]; my /æ/ I believe to be far more like (cardinal) [a] than [æ]; my /u/ seems to be a kind of central/lax front vowel of the order of [ʉ], quite far from [u], my /aɪ/ is far more like [ɑɪ] or [ʌɪ], and my /e/ is far more like [ɛ] than [e]. Now, I understand that phonemic symbols are merely conveniences, and aren’t needfully meant to convey any underlying phonetic reality. I also understand that, historically, it was also more difficult to type, for instance, the IPA symbol for a close central rounded vowel, ʉ, than u.”

But he’s still very unhappy about it.

I replied along the following lines:

“When I first started phonetics myself, nearly fifty years ago, I had the same thought as you about /ʌ/: that it would be better written /ɐ/. I made a point of transcribing it like that in the transcription assignments I was set by my phonetics teacher.

But when I came to be a phonetics teacher myself, and to publish books, it seemed better to stick with the same transcription that other people use. There are millions of people around the world who know that /ʌ/ means the STRUT vowel of English; there are a few thousand, at most, who know or care anything about the cardinal vowel system.

The same, mutatis mutandis, applies to /æ/ (better written /a/?) and to /uː/ (better /ʉː/?).

Furthermore, if we want the same transcription system to apply to a wide range of different varieties of English, there are strong arguments in favour of sticking with /æ/ and /uː/.

It is possible that in another fifty years the discrepancies will have become too great: the tectonic plates will shift, and some new influential phonetician will establish a different notation. But not me.”

ɐ Last Wednesday I mentioned hearing a radio presenter pronounce Gauguin with the English vowel /aʊ/ rather than the usual /əʊ/. Evidently, the foreign-language spelling au is something of a trap. On Sunday I heard another radio presenter, a BBC person this time, repeatedly pronounce the name of the Welsh parliamentary constituency Blaenau Gwent as /ˈblaɪnaʊ ˈgwent/.

The Welsh plural ending -au (as in blaenau ‘tops, heights’, plural of blaen) has various pronunciations in the varying regional forms and stylistic levels of Welsh: in careful formal speech [ai], or in the north [aɨ], and in everyday speech more usually [e] or [a], or in Anglo-Welsh even [ə]. But nowhere is it [au].

The only people who might say /ˈblaɪnaʊ/ are those who do not know Welsh and who make a false inference on the basis of what they know about the relation between spelling and sound in German or some other irrelevant language.

Reading rules for au in non-English words: in French words /əʊ/ (reflecting French [o]: gauche, mauve, chauvinist); in German, Spanish etc words /aʊ/ (Frau, Spandau, gaucho); but in Welsh words /aɪ/. So it’s Blaen[aɪ] or Blaen[ə] Gwent. The Welsh count 1, 2, 3 as un, dau, tri, which sounds like English een, die, tree.

What makes it worse is that the hour-long programme was entirely devoted to the topic of Wales and the Welsh language.

Here are some more of Michael Ashby’s photos of people attending Friday’s celebrations.

Friday was a wonderful and memorable day for me. Here are some first pictures of speakers at the celebrations, courtesy of Michael Ashby.

Today we hold my retirement celebrations at UCL. We have a varied programme of talks, and it should be an enjoyable day. Several of the overseas guests have already arrived and come in to say hello.

Then on Monday we start the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics, which runs for two weeks. Here’s the timetable.

A week ago I wrote about the difficulty of accounting for the tonicity in

If they can 'sort it 'out for them\/selves, | we’d 'like to 'see them \do so.

The problem, I said, was that do so consists of function words. We expect function words to be unaccented unless they are contrastive. So why does do remain accented? In a neutral reading, it bears the nucleus.

I’ve had two replies. One was from Jack Windsor Lewis, who says, “Surely you've supplied the answer to your question yourself. Here do so is indeed contrastive with not sort it out implied in the if”.

Well, yes, Jack. But what I want to have is a set of rules that can be applied by an automaton (a speech synthesizer) or an EFL student, rules which will produce the correct intonation pattern. And the rules as I formulate them seem to lead to the pattern

If they can 'sort it 'out for them\/selves, | we’d 'like to \see them do so.

— which is possible, but in fact marked. My rules tell me to accent an auxiliary verb only if it is the bearer of contrastive tense or contrastive polarity, as in

In 'earlier times they ne\/glected it, | but 'nowadays they \do sort it out.

I 'look to them to 'sort it /out | and they \do sort it out.

— but the do in the example we started with is not an auxiliary but a pro-verb (or you could call do so a pro-VP).

The other reply was from Tamikazu Date, posting in the Supras group. He implies that this tonicity is essentially an intonation idiom, which he compares with Bolinger’s examples

— in which he considers the accenting of the repeated verbs buy, leave also to be idiomatic. This is quite true: the usual rules would lead us, wrongly, to expect

Hey ho.

Ten days ago I remarked that “English people do not know much about the pronunciation of foreign languages, except to some extent French”. Sometimes one has to wonder even about that.

An announcer on Classic FM radio yesterday evening referred to the painter Gauguin not as [ˈgəʊgæ̃], which is the usual semi-anglicized pronunciation used by educated English people, but as [gaʊˈgæ̃]. It’s not so much the American-style end-stressing of the French name that caught my attention as the interpretation of orthographic au as if it were German rather than French. (Cf Spandau.)

Mind you, the convention that maps French /o/ (orthographically au, eau, ô etc.) onto English /əʊ/ is rather odd. It would be phonetically more accurate to equate it with English /ɔː/. And in the cases spelt au, including Gauguin, this would also coincide with English orthographic habits. So, [ˈgɔːgæ̃], anyone?

I have a confession to make. Now that we are out of term and I am on the verge of retirement, I sometimes come home a bit early and at 17:45 slump down in front of the television to watch Judge Judy on ITV2. For those who don’t know this programme, it features “real cases, real people” in the American small-claims courtroom of Judge Judy Sheindlin, a sassy New Yorker and a very perceptive lawyer.

The programme also offers excellent opportunities to observe popular American linguistic usage in the mouths of the unscripted witnesses. (I had never previously realized the extent to which ordinary Americans use non-standard verb forms, such as I had went, she had wrote.)

In the UK we get not the current series but reruns of old shows. The programme shown yesterday (some five or six years old) had as one of the defendants a Californian black man with a pronunciation feature I have never noticed before and never seen referred to: for the cluster /θr/, as in throw, through, he pronounced a kind of pharyngealized dental plosive, really rather like an Arabic emphatic t, so [t̪ˁoʊ, t̪ˁuː]. I don’t know if this was a personal idiosyncrasy of this particular speaker, or whether other people do it too. Anyone got any comments?

By the way, you can listen to short sound clips of Judge Judy herself here.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Archived from previous months:

Current blog my home page