DEPARTMENT OF SPEECH, HEARING & PHONETIC SCIENCES UCL Division of Psychology & Language Sciences |

|

My phonetic blog — July 2006John Wellsemail: To see the phonetic symbols in the text, please ensure that you have installed a Unicode font that includes all the IPA symbols, for example Charis SIL (free download). |

|

| Monday 31 July 2006 | In a phonetics class earlier in the year I was discussing the pronunciation of words such as roll, cold, bolt. I mentioned the special vowel quality [ɒʊ] that some English people use in these and other words where the vowel is followed by a morpheme-final or preconsonantal /l/, a quality so different from their usual [əʊ] (as in grow, code, boat) that they are reluctant to view it as an allophone of /əʊ/. You can hear the difference if you ask such speakers to pronounce, for example, wholly and holy, or rolling and Roland. I demonstrated that unlike such speakers I personally use pretty much the same [əʊ] quality in all these words, no matter what the following consonant might be. In support of this contention (which surprised some of the students), I recounted how, when I was a small boy and couldn’t sleep one night, my father told me the Bible story of Moses and the burning bush (Exodus 3). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the words of the Authorized Version, God spake unto Moses from out of the midst of the bush and said, “Draw not nigh hither: put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground”. But I heard this as hole-y ground, ground with holes in it. (If Moses kept his shoes on, I thought, perhaps he would get them caught in the holes.) This implies that my late father pronounced [ˈhəʊli] holy ‘sacred’ and [ˈhəʊli] hole-y ‘containing holes’ identically — like me, and unlike the speakers mentioned above. In the phonetics class this led on to a discussion of the concept of Mondegreens, in connection with which I cannot do better than refer you to this Wikipedia article. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Friday 28 July 2006 | A Hungarian reader of this blog downloaded and installed Mark Huckvale’s Unicode Phonetic Keyboard, and this in turn inspired him, though not a phonetician, to attempt a phonetic transcription of a video clip, a news item from the BBC website. The result is an impressionistic transcription of some interest. Overall, his achievements as a beginner in the subject are pretty impressive. Admittedly, there are the typical mishearings to be expected from any Hungarian EFL learner: confusion of [v, w, u], of [e, æ], and of [æ, ʌ, ə, ɜ]; also of voiceless/voiced obstruents in final position. But there were also errors attributable to being misled by the oddities of English spelling, as for example when the [ʌ] in done, month was heard as [ɒ]. More important than the minutiae of phonetic detail are the cases where he misheard and therefore could not properly understand the content. Proper names are always problematic: he heard Surrey as sorry and Sally-Ann as Solyan (?). The expression a Lloyd’s bar came out as alloyed bar, while various bars was heard as very sparts (?). The BBC’s Crimewatch programme was heard as Prime One. And at that stage was heard as that page. You can access my correspondent’s efforts (in white and green), and my own fair copy (in yellow and grey), as a Word document. It includes a link to the video clip. |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thursday 27 July 2006 | Two little intonation examples today: First, a tonality minimal pair. (i) Surprisingly, | few people were interested. (ii) Surprisingly few people were interested. In (i), surprisingly is a sentence adverb meaning something like ‘you’ll be surprised to hear what I’m going to say’. In (ii), it is an ordinary adverb modifying few, ‘fewer people than you’d expect’. The grammatical difference is reflected in the intonation. The second example is one that I can’t quite explain. It was taken from a broadcast discussion about whether people should solve their own problems or should expect outsiders to help. If they can sort it out for themselves, |we’d like to see them do so. The problem is this: do is a “pro-verb”, a dummy verb. The expression do so stands for sort it out for themselves. Hence it consists of function words rather than content words. With certain exceptions, we expect function words to be unaccented unless they are contrastive. So why does do remain accented? In a neutral reading, it bears the nucleus. If they can 'sort it 'out for them\/selves, | we’d 'like to 'see them \do so. Compare also If you 'want those \/shoes, | 'go ahead and \buy them. If you 'want to \/buy them, | 'go ahead and \do so. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

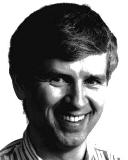

| Wednesday 26 July 2006 | The Guardian newspaper a few days ago carried the following correction: A mishearing led us to quote the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips as saying that “anybody who’s been in the therapy profession for any length of time will know that there have always been crazies”. In fact, he was referring to crazes. I am one of those who pronounce crazies and crazes identically, as [ˈkreɪzɪz]. They are absolute homophones for me, so I can sympathize with anyone who “mishears” one for the other. However many other native speakers of English — the majority, I should think — make a distinction between the two. Either their happY vowel (the final vowel in crazy) is tenser, [i], or they use a schwa in the plural ending after a sibilant (crazes), or both. That is why modern pronunciation dictionaries, including LPD, use the special symbol [i] for the weak happY vowel. It covers both an [iː]-like quality, for those who use it, and an [ɪ]-like quality, for those like me who use that. So we write crazies as /ˈkreɪziz/, crazes as /ˈkreɪzɪz/ (or /ˈkreɪzəz/). Other potential homophones to test: bandied — banded, studied — studded, taxis — taxes, Rosie’s — roses. |  Adam Phillips | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tuesday 25 July 2006 | Ever since being diagnosed with a heart problem two years ago I have been in the habit of attending the Cardiac Support Group organized by my local hospital. As well as providing useful advice and reports of the latest research, it gives me excellent exposure to medical language and its idiosyncrasies. At yesterday’s meeting I collected a new example of word-internal intrusive r: meta-analysis. The speaker, a general practitioner, used this word several times, and each time pronounced it as /ˌmetərəˈnæləsɪs/. A meta-analysis, in statistics, is a large study that combines the results of several smaller studies. Actually, as the classicist in me protests, this word is not well-formed from the point of view of Greek. In classical Greek prefixes ending in a vowel, such as meta- (but also para-, ana-, epi- etc.), lose the vowel if the following stem has an initial vowel (or /h/ plus a vowel). We see this in metempsychosis and metonymy, and also in method. So the word ought to be metanalysis. Indeed, the second edition of the OED does not include meta-analysis, but only metanalysis. Interestingly, this latter form, and with it the verb to metanalyse, belongs not to statistics but to linguistics. For example, Randolph Quirk, in his 1962 book The Use of English, wrote that “when the French word crevice ... was introduced into Middle English, its connexion with ‘sea food’ caused people to metanalyse the final syllable as -fish (‘crayfish’)”. Somehow it’s not surprising that the linguists get the Greek right, while the statisticians, medical or otherwise, don’t. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monday 24 July 2006 | On Saturday I went to Reading for Jane Setter’s birthday party. She and her husband Rob live in an attractive stone-built house in the middle of the town. Any visitor to Reading will be struck by the road signs everywhere pointing to the Madejski stadium. Why does the stadium have a Polish name? And how do people pronounce it? Reading Football Club’s stadium is named after John Madejski, one of the wealthiest people in the UK, the club’s benefactor. He was born in Britain, with an English mother, but his father was Polish, an airman who was stationed here during World War II. As a Polish name, Madejski is pronounced exactly as spelt. The Polish diphthong written ej is similar to the English vowel in face, so the name would anglicize very easily as /məˈdeɪski/. However, English people do not know much about the pronunciation of foreign languages, except to some extent French. So they do not expect the letter j to stand for anything other than /dʒ/ or (in foreign words) /ʒ/. And */məˈdeʒski/ would violate English phonotactics and thus be impossible. In fact, I am told that the usual pronunciation of the name in Reading is /məˈdʒeski/, as if spelt Madjeski. The metathesis makes it pronounceable. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

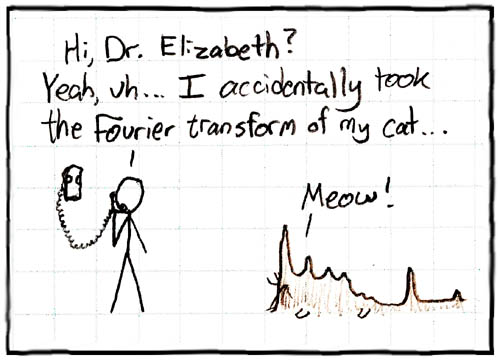

| Saturday 22 July 2006 | Two items from the ever-interesting Language Log. The cartoon is for my colleagues in experimental phonetics and speech recognition.

And today’s entry concerns phonetics: We feel sad because we say ü. Read it! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Friday 21 July 2006 | As some of you will know, two weeks from today the UCL Department of Phonetics and Linguistics will be holding a one-day conference in honour of my retirement. There will be morning and afternoon sessions devoted to talks by my friends and colleagues, some from Britain, some from further afield. The talks will be followed by a reception. I look forward to seeing many friendly and familiar faces there. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This will be a kind of preamble to the annual UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics, which starts the following Monday and runs for two weeks. It looks as if we shall have between 120 and 130 participants. This will be the last time that I shall act as its Director. |  | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Current financial stringencies mean that the chair I vacate at UCL will not be filled immediately, indeed perhaps not for some time. But at least the department continues to flourish. Things are much worse at Christian-Albrechts-Universität, Kiel, in north Germany. Klaus Kohler, who 35 years ago set up the Institut für Phonetik und Digitale Sprachverarbeitung (Institute of Phonetics and Digital Signal Processing), retired as its chair some years ago. Now, upon the resignation of his successor Jonathan Harrington, the university has decided to close down the entire department (institute). A petition to save it is circulating (details). Kiel was the venue for the IPA’s 1989 Kiel Convention, when phoneticians from all over the world met to establish the Association’s Alphabet and Chart in its modern form. Strangely, this is not mentioned in the account of the institute’s history on its website. |  | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thursday 20 July 2006 | From yesterday’s Guardian newspaper: “Y speling proplee is so ovar8tedJohn CraceNo wun cairs if ve chavs cant spel or doan no how to punkt - ah fuk it, doan no wair to put commerz - but shorely ve toffs kan do al vat, innit? A parent lee not. A cord ing 2 an artikal in ve Harro skool magazeen, pew pills r ge ting top marx in Ingerlish at GSCE d spite beeung unabul 2 spel simpul words corektlee. Haro, wich introd, nah, star ted a litracy test 4 sixff formaz aftah teecherz notisst mega erraz in vair wurk as foun vat too thurds - aka quit a lot - wot faild ad allredy go a NA or NA* a CSGE. "Cant spel simpul wordz or punkty8 a simpul sen10ce, bui kan stil geh a NA?" sed Tom Wikcson, Ingerlund teech. "Vat karn b write. Wel, yeh like, a Tarot wee freekwentlee fine vat kan b ve kase." I don't know if you're bored of the gag by now, but I am, so we're moving back to a written English with which Wickson would be more comfortable. But why should anyone get that bothered? Just how much trouble did you have reading the first two paragraphs? Very little, I would guess. In fact, I could almost certainly have made things far trickier and you would have still had no problem. According to an article that appeared in Nature in 1999 and an unpublished dissertation on proofreading, written by Graham Rawlinson of Nottingham University in 1976, as long as the first and last letter of any word are correct, it doesn't matter what order you place the rest, because the word will always be understood. Try it. Whoo culod psas upp thhe cahcne too wrtie copmelte rubisbh inn thhe itneretses off adamicec raseecrh? So if I can still make myself clearly understood by misspelling every word, why do so many people get so hung up on the precision of language? What makes English sacred? The language of Chaucer and Shakespeare bears only a passing resemblance to Martin Amis and Julian Barnes, and none at all to James Kelman. "Correct spelling is only concerned with disciplinarianism and archaeology," says John Sutherland, Emeritus Lord Northcliffe Professor of Modern English Literature at University College London (a title that would not be undermined if you spelt it wrong). "It merely tells us whether a word has a Latin, French, Germanic or Gothic derivation. I'm with George Bernard Shaw, who left his fortune to the quixotic cause of rationalising the English language. "English is just a dumpbag of loan words and we should be aiming to be like the Spanish, who alter every word to fit the sound of their language. The Guardian could create a precedent by renaming itself the Gardien." Wel, it wuld maek er chaynj fum the Grauniad. |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wednesday 19 July 2006 | As I got off the tram on my way home yesterday, the recorded announcement went as follows. \/This tram | is for 'Elmer’s \End. The \/next stop | will be 'Morden \Road. Deconstruction of the intonation patterns: You know this is a tram, so the concept tram is ‘given’. We focus instead on the contrast (therefore fall-rise tone) between this tram, whose destination we shall now tell you, and other trams that may be going to other places. We declare (therefore fall tone) its destination. You know you’re at a tram stop. So the concept stop is given. We focus instead on the contrast (fall-rise) between the next one and this one or other ones. We declare (fall) its identity. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tuesday 18 July 2006 | Here is a first attempt at putting a short video clip in this blog. If you click on the icon alongside, you might be able to see an 11-second clip of my nephew Mark in his wedding speech ten days ago. At this point he is teasing his best man with scurrilous allegations made in jest. (The clip is in .ASF format, which Windows Media Player can play. But I don’t know about other software.) It includes an excellent example of an intrusive /r/ (spa[r] in Covent Garden) and two instances of stress shift (accidentally, fifteen).

Half the guests didn’t get the joke, which turns on the fact that a ‘Brazilian’ is not only someone from Brazil but also a Brazilian Wax pubic hair treatment. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monday 17 July 2006 | As I was jogging in a local park, a man coming the other way asked me, You 'haven’t got the /time on you, have you mate? Since I was indeed wearing a watch, I duly answered him, E'leven fifty-\seven. The wording and intonation of his question was appropriate for the situation of an English person addressing a stranger. But an EFL student would probably have cast the question differently: 'What’s the \time? — which in this context would have sounded rude. Why is this? We use the simple wording and the fall when we wish to be businesslike with someone we are already talking to. We would also use this pattern if repeating the question to someone who seemed not to have heard it, or who was refusing to answer, or if we were otherwise annoyed at their non-cooperation. But when starting a conversation, particularly with a stranger, we prefer to be indirect. The negative statement followed by a reverse-polarity tag question in the same intonation phrase does the job nicely. You 'haven’t got the /time on you, have you mate? Alternative polite formulae in BrE would be 'Have you got the /time on you by any chance? Ex\/cuse me, | d’you 'happen to know what /time it is? \/Sorry, | d’you 'have the /time? 'Got the /time, mate? Ex\/cuse me, | I was \wondering, | 'what /time d’you make it? Some speakers (particularly younger ones?) might alternatively use a highish fall-rise instead of the rise. Americans would probably not be so indirect. And they would not use the BrE working-class non-deferential male-to-male vocative mate, but probably bud(dy). The formulae you sometimes hear from speakers of Russian, involving a negative question, 'Haven’t you got the /time on you? 'Don’t you know the /time? sound like accusations and are therefore very inappropriate ways to ask the question. They are reproaches to someone who is late. |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

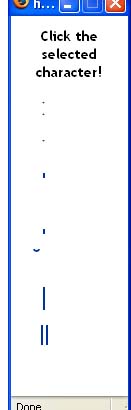

| Friday 14 July 2006 | Further to yesterday’s dicussion of CharWrite©: it appears that it is after all possible to enter stress, length, and tone marks, though this fact was undocumented. Following a query from me, the instructions have today been revised to include the following: ‘If you would like to enter a tone mark, type a single left quote "`" and right-click. For length or stress marks, type bar "|", and for other diacritics type tilde "~".’ On a quite different issue: Graciela Freiberg, a student from Argentina posting (with some difficulty) on the Topica phonetics email list, wants to know how to account for the word "system" when we say "the English intonation system". ‘I know Brazil talks about the system of English intonation,’ she says, ‘but why is it called a system?’ Tami Date very appropriately refers her to Paul Tench’s book The intonation systems of English, and Richard Cauldwell (of Streaming Speech fame) says ‘System(atic) in the technical sense of: (A) having a finite set of either/or options (e.g. a syllable either is, or is not, prominent) (B) covering all the data - not just episodes such as questions and lists’. Graciela is not the only one having difficulty in getting the Topica phonetics list to accept messages, so here’s my comment. I’m not sure what Richard means in his (B) clause, but his (A) clause is exactly right. In linguistics, a system is a fixed set of choices. Nouns in many (but not all) languages exhibit a NUMBER system — every time we utter a noun we have to make it either singular or plural. Verbs usually display a TENSE sytem (present vs. past, etc.). Most people analyse English verbs as also displaying an ASPECT system (progressive vs. non-progressive, perfective vs. non-perfective). Similarly, ever since Halliday’s work in the 1960’s, people analysing English intonation have identified three systems in operation:

The claim here is that in these three respects we make a succession of choices all the time as we speak, as we decide how to structure our material, what to focus on, and what attitude (etc.) to express towards what we are saying. Some would claim that this is all also part of a complicated battle with our interlocutor(s) for control of the conversation. |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thursday 13 July 2006 | Two days ago I discussed input methods for Unicode phonetic symbols in word processing. Another ingenious method is called CharWrite©. It works for all Unicode characters based on the Latin alphabet, not just IPA symbols. To enter a character, you type the plain alphabetic letter similar to the letter you actually want. Right-click, and a box appears showing the same letter with various diacritics, and phonetic symbols that resemble it. Click on the one you want, and it appears in your document. Alternatively, you can double-left-click and bring up an IPA chart to choose your character from. You can try it out on the demonstration web page, or download it to store it on your own computer. (It seems to be not an executable program, but a web page that you make available to yourself off-line.) CharWrite© works nicely for writing a Word document. But to use it in composing a web page, I think you would have to copy the text it generates into Word, then Save As HTML, then open as a text document and copy the character entities. As far as I am concerned, this is too fussy for practical use. Further, CharWrite© has a number of oddities. It does not recognize the IPA length mark as being similar to the ordinary colon. The length mark, the stress mark, and the secondary stress mark can only be entered by picking them out on the IPA chart. The STRUT vowel (ʌ, cardinal 14) is treated as a variant of a, not of u or v (which is where I would expect to find it). The method comes courtesy of the Linguist List. |  This is a picture of what is evoked by right-clicking on “o”, not an actual functioning selection box | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wednesday 12 July 2006 | The German company Zeitgeist Media wrote asking me, in my capacity as President of the Simplified Spelling Society, to reply to a few questions. Here they are, with my answers [and a few extra explanations, in square brackets]. Q Why do you think English spelling should be reformed? A Adopting a more regular spelling system would save future generations the unnecessary effort of learning the irregularities and unpredictabilities of our current orthography. Q Would a spelling reform be beneficial for the role of English as world language? A It would save time and effort for everyone who has to learn English as a foreign language. It would also help to eliminate mispronunciations based on the current spelling. For example, broad does NOT rhyme with road. If we spelt it braud, EFL learners would know how to pronounce it correctly. If we changed the spelling of front to frunt, people would not think it rhymes with font. [brɔ:d, rəʊd, frʌnt, fɒnt] Q Which changes in English spelling do you consider to be most important? A

[wɪnd, waɪnd] Q Which one of the proposals do you consider most promising ("Cut Spelling", "New Spelling" etc)? A The best worked-out scheme that I have seen is Cut Spelling. Q What does the Simplified Spelling Society do in order to raise awareness of the problems with English spelling in the public? A Write articles and books, do radio and television interviews, maintain a website, organize meetings. Q Do you think a comprehensive spelling reform of English will ever come into effect, and why? A I am not sure that a 'comprehensive' reform is what we need. I prefer a gradualist, minimalist correction of the worst anomalies of the present system. Young people have invented their own do-it-yourself system in text messaging. They write u for you, r for are, sum1 for someone, 4 for for, gr8 for great etc. But it has not been consistently worked out. Within my own lifetime we have given up to-day in favour of today, shew in favour of show. I see no reason why such gradual reform should not continue, but preferably rather faster. Your recent gradualist, minimalist German reform has corrected the ambiguity associated with the length of the vowels of Fuß, Nuss. But it has left untouched the similar ambiguity of Pferd, Berg. [fu:s, nʊs. Before the 1996-2005 reform of German spelling, Nuss was spelt Nuß, giving rise to the anomaly of a short vowel before a the 'single' consonant letter ß; now the vowel is followed by two consonant letters. A vowel letter before rC is still ambiguous as to length: pfe:rt, bɛrk. To remove the ambiguity, Pferd would need to be spelt Pfeerd or Pfehrd.] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

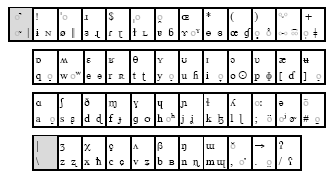

| Tuesday 11 July 2006 | Entering Unicode IPA symbols when writing a document, sending an email, or composing a web page calls for special techniques, since they cannot be entered directly from the keyboard. I have a web page devoted to the subject (and another one), but some people have devised other, hopefully simpler, ways of doing it. SIL offers a special keyboard facility, though several people have told me they found it difficult to install and use.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

My colleague Mark Huckvale has devised another keyboard facility, Unicode Phonetic Keyboard, which is simple and straightforward. The result is like installing a foreign-language keyboard: you switch into it and out again by clicking a button. When you’re in phonetic mode, you use Shift and AltGr combinations to access the symbols not normally available from the keyboard. The key assignation choices are based on the familiar SAMPA equivalents. (There seems to be a glitch at the moment in that it is sometimes difficult to persuade the keyboard to revert to the normal character set.) A different approach is represented by two enthusiasts who have produced “phonemic typewriters”, virtual (screen) keyboards covering just the IPA symbols needed for phonemic transcription of RP. |  (full-size, as .pdf) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

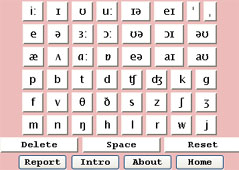

One of them is Pete MacKichan’s Phonemic Script Typewriter. This displays a keyboard on your screen, and you “type” by clicking on each symbol in turn that you need. The output can be a string of characters for copying into a document, or a string of HTML codes for copying into a web page. Kayoko Yanagisawa tells me that students on the PHONLINE course find this a useful facility. |  | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

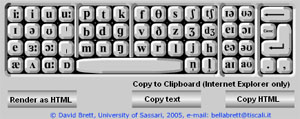

The other is David Brett’s Unicode Phonemic Typewriter, which works in the same general way. Both provide single keystrokes for English diphthongs and affricates, but MacKichan symbolizes the palatoalveolar affricates as ligatures, ʧ ʤ, while Brett symbolizes them as two-character sequences tʃ dʒ. Brett provides for syllabic n̩ and l̩, and also for the neutralization symbols i (happY) and u (thank yOU) that most of us use nowadays; all of these are missing in MacKichan. Both authors use a colon instead of the proper IPA lengthmark [ː]. They would perhaps justify this on the grounds that the popular browser IE4 has a glitch which prevents the proper display of the latter. Brett’s HTML coding is faulty in one minor respect, but he assures me he will put this right. |  | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monday 10 July 2006 |

On Saturday my nephew Mark Wells was married to Jane Littlewood at a village parish church in Kent. He is Director of Light Entertainment for a national television company: you can see something of his work here (to find his name, scroll all the way down). It was a marvellous and memorable day. Katherine Jenkins sang during the signing of the register. She sounded wonderful and looked stunning. My own small part was to read one of the readings. Near the end of the marriage service, as we all said the Lord’s Prayer together, it suddenly struck me — apropos of compression and its variability in English, unlike in Swedish (blog, 4 July) — that as a small child I was taught to recite ...Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil; /ˈli:d əs ˈnɒt ɪntə tempˈteɪʃən, bət dɪˈlɪvər əs frəm ˈi:vəl fə ˈðaɪn ɪz ðə ˈkɪŋdəm, ðə ˈpaər ən ðə ˈglɔ:ri, fər ˈevər ən ˈevə, ɑ:ˈmen/ but never .../dɪˈlɪvrəs frəm ˈi:vəl/... nor .../fər ˈevrən ˈevə/... even though those are perfectly valid compression options in English. Yet I was taught to say power as a single syllable / ðə ˈpaər ən ðə ˈglɔ:ri/. |  Katherine Jenkins (r.) with my niece, sister-in-law and brother  The happy couple Friday 7 July 2006

| From yesterday’s Guardian: Cheshire PoW's dialect recording turns up in Berlin 90 years onby David WardThe recording begins with a swish and a crackle and then a strong male voice is heard speaking in a solid northern accent: "There was a man who had two sons ... " No one knows who the speaker is. All that is certain is that his home was in Alderley Edge, Cheshire, and that his reading of the biblical parable of the prodigal son was recorded 90 years ago in a prisoner of war camp as the first world war raged. The recording, made by an Austrian academic with a deep love of British dialects, has come to light with the help of dogged research and some good luck and is now available for all to hear on the Alderley Edge village website. "There are 1,564 entries for Cheshire in the British Library catalogue and I looked at every one," said John Adams, project manager for the website, launched by Manchester Museum, part of the University of Manchester. "Almost at the end, I found a reference to mundart, the German for dialect." The catalogue entry led to a book in which a researcher had transcribed the dialect recording into the international phonetic alphabet. Mr Adams managed to track down the recording made on shellac to the Humboldt University library in Berlin, which had just digitised it the week before. "When I heard the first crackle, the hairs rose on the back of my neck. I realised the voice I was hearing had not been heard for 90 years." The recording was made by Professor Alois Brandl, an Austrian based at a Berlin university. He also worked in London, wrote a commentary on Shakespeare and may have made dialect field trips around Britain. The soldier says "feyther" for father, "fund" for found, "deein" for dying; the prodigal "cum wom" (came home); his brother returned from "t' fields but wudna go in to the house".

|

| "You get a sense that this man is trying to conjure up a sample of dialect," said Martin Barry, lecturer in phonetics at the University of Manchester. "There is no way of telling if ordinary vernacular speech at that time would have been larded with such touches." Listen to the recording on the Story of Alderley Edge website

|

Thursday 6 July 2006

| Yesterday evening I watched a fascinating television programme, The Castrati, on the digital channel BBC4. The co-presenter was Prof. David Howard of the University of York, whom I know well from the time when he was on the staff of UCL Phonetics & Linguistics. In this one-hour programme, part of a series The century that made us, David described how the human voice works, with particular reference to the castrati who played such an important role in eighteenth-century music. Taking Handel’s well-known aria Ombra mai fu, he attempted to recreate the castrato sound electronically, by morphing the voices of boy trebles with those of adult males, associating the acoustic characteristics of the boys’ larynxes with those of the men’s upper vocal tracts. Here is David’s web page describing the work. The programme will be repeated on Sunday at 23:50, still on BBC4.

Wednesday 5 July 2006

| Further on the matter of (non-)compression, Jack Windsor Lewis writes: “There are signs of a fast increasing minority tendency for General British speakers to favour the use of schwa plus (unsyllabic) consonant where previously syllabic consonants were the norm, eg in cotton, garden, bottle and struggle, and even increasingly in such items as assembly, doubly, gambling, cackling etc, for which it is doubtful that they ever previously contained a syllabic consonant. These last would strike many as strange but there can be no doubt about their increasing proliferation even though it doesn’t seem to have been much commented on as yet. There evidently has to be a related word with a syllabic consonant to trigger this, so that eg duckling, madly, ugly, Wembley etc are not usually affected but eg buckler, burglar, butler, inkling, spindly, stickler etc may well soon be increasingly heard with an anaptyctic schwa by some GB speakers.” I think Jack’s observations are correct. I do quite often hear three-syllable schwa-containing pronunciations of words such as threatening, doubling, gathering (though I don’t think I’d ever use such a pronunciation myself), and even of simpler. I’ve never yet heard a trisyllabic version of gently, though it’s not uncommon in subtly.

Tuesday 4 July 2006

| Olle Kjellin writes in connection with epenthetic schwa (blog, 27 June): In contemporary Swedish we have a rule that states that an L, N or R after a syllable with a final obstruent should be preceded OR followed by a vowel, but not both, e.g.:

This seems to be like the English process that I have called compression (in LPD and elsewhere), except that it is categorical (compulsory) where the English one is in some cases variable (optional) or disallowed. The crucial point of compression is that the number of syllables is reduced by one when a syllable beginning with a vowel follows. In English (treating potential syllabic consonants as phonetic variants of schwa plus the consonant):

In English this process is blocked if the following vowel is strong. There is no possibility of compression in the following (though there is the possibility, indeed the likelihood, of a syllabic consonant):

There are other cases, too, where it fails. Vitally does not rhyme with nightly:

Lots more examples in this lecture handout. More on this tomorrow.

Monday 3 July 2006

| Here are some humorous word definitions heard on the BBC Radio 4 programme I’m sorry, I haven’t a clue (listen to it here), with a phonetic commentary.

| |

| This show is famous for its sexual innuendo delivered straight-faced by the chairman Humphrey Lyttelton, a speaker of immaculate RP.

| Saturday 1 July 2006

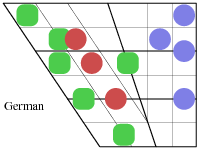

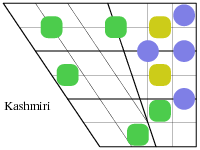

| On Jack Windsor Lewis’s website, among many other goodies, there is a page devoted entirely to vowel diagrams of different languages. These are “vowel system diagrams in colour”. The convention he applies is that front unrounded vowels are shown as square green blobs, back rounded vowels as circular blue blobs, front rounded vowels (less frequent in the world’s languages) as circular red blobs, and back unrounded vowels (even more unusual) as square yellow blobs. Vowels of the [ɑ] type are sensibly treated as systemically front, even if phonetically back, so shown in green. The only thing missing is some sort of shading to show vowels that are contrastively

A hundred and twenty different languages are represented, covering most parts of the world (though as far as I can see there are no New Guinea or Australian languages). A fascinating page for every phonetician. Read the disclaimers at the top.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Archived from previous months:

my home page