DEPARTMENT OF SPEECH, HEARING & PHONETIC SCIENCES UCL Division of Psychology & Language Sciences |

|

John Wells’s phonetic blog — archive 15-31 March 2007email: To see the phonetic symbols in the text, please ensure that you have installed a Unicode font that includes all the IPA symbols, for example Charis SIL (free download).

Browsers: Some versions of Internet Explorer and Safari have bugs that prevent the proper display of certain phonetic symbols. I recommend Firefox (free) or, if you prefer, Opera (also free).

|

|

| Saturday 31 March 2007 | The late greatNot everyone knows about Olle Engstrand’s Phonetic Portrait Gallery, Pioneers in Phonetics and Speech Research. This page offers pictures of nearly 150 phoneticians, the pioneers of our subject. Here you can find photos of my late UCL colleagues Daniel Jones, Hélène Coustenoble, Dennis Fry, A.C. Gimson, and J.D.O’Connor, — people I am proud to have studied under — as well as of such luminaries as Paul Passy, Ferdinand de Saussure, Henry Sweet, Kenneth Pike, David Abercrombie, Shiro Hattori, and Edward Sapir. The only restriction seems to be that no living person is shown. The gallery has been “under construction” for years and years. It may be some time since it was updated, because there is no picture of, for example, Peter Ladefoged, despite his having died over a year ago. The page is very slow to load, since it has all the photos on a single enormous page. (To prevent the same thing happening with this blog, I show only ten or so days at a time, relegating older entries to the archive pages.) All the pictures I display here appear to be in the public domain. Some of the others are acknowledged to a particular photographer.

Now you can see why I like, wherever possible, to show pictures of the (still living) colleagues who have written to me for this blog or whom I write about in it. I hope that when we are all dead and gone the compiler of this gallery or its successor will make use of some of the pictures. To see more, go to www.ling.su.se/fon/phoneticians/Gubbar.html |

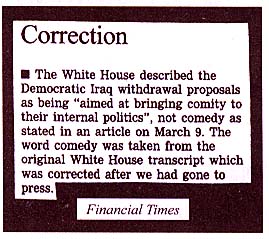

I found this clipping in Private Eye.

It just shows what t-voicing leads to.

(Do you know the story of Atom and Eve?)

The British Library has made available a new collection of sound recordings under the above title. According to their website, It sounds very useful. Obviously, this is where I must send those would-be writers of essays and dissertations on English accents who ask me for help because unfortunately, being overseas, they don’t have access to actual speakers.

The leader writer in yesterday’s Guardian newspaper got quite carried away.

I’m afraid that this still needs a phonetician to explain that ‘flatter’ means a front as opposed to a back vowel. The southeast and RP have [ɑː], the Cornwall-to-Norfolk strip (which is discontinuous) has [aː], and the north has [a].

Thomas Widmann, who works for Collins dictionaries and is the author of a multilingual blog, writes:

This is essentially what the first edition of the OED did, using notations such as ă. It was abandoned in later editions.

In some words (not panda) this kind of analysis is supported by the use of strong vowels in singing. Transcribing angel as /ˈeɪndʒĕl/ (where ĕ = weakenable e) could be justified on these grounds, even though in all kinds of speech other than singing we say /ˈeɪndʒəl/.

But it is precisely cases such as the second syllable of panda that present an interesting case. There is no style of speech in which we use anything other than /ə/, and no grounds other than orthographic for choosing one of Thomas’s alternatives rather than another. As long as it remains a weak vowel, the final vowel of panda contrasts only with what I write /i/ and /u/, i.e. the vowels of happy and thank you. Compare panda and handy. Hence, as long as we know we are in the weak vowel system, schwa does indeed represent a neutralization of /e, æ, ɒ, eə, ɑː, ɔː, ɜː/, as we see in the strong/weak alternation of them, at, of, there, are, for, sir.

Actually, there’s a problem with /e/, which in the endings -ed, -es, -est weakens not to schwa but to /ɪ/ for most speakers of RP etc. (In closed syllables there is a slightly larger weak-vowel system, which includes /ɪ/.) Such speakers formerly weakened it to /ɪ/ in -less, -ness, but now mostly weaken it to /ə/. So we have the awkward anomaly that /e/ can have two different neutralization forms, even for the same speaker.

ə However, the main argument against this line of thought is rather different. It is that we never know from the general structure of a word whether a given unstressed syllable will select its vowel from the strong system or from the weak system. Alongside words like gymnæst (strong system) we have words like modɪst (weak system). Think about the unstressed final syllables of phoneme, Kellogg, cuckoo, syntax, torment (n.) — all strong. No neutralization there! Chomsky and Halle have some pointers to what’s going on, but in many cases it remains arbitrary whether or not vowel weakening occurs.

In this respect English differs strikingly from, say, Russian, where weakening is highly predictable once you know where the stress is located.

PS: Thomas also tells me that he read my book Lingvistikaj Aspektoj de Esperanto in a Danish translation, and that it was his first introduction to IPA and also to Greenberg’s language typology, which he then took as the topic for his MA dissertation. He says ‘Ĝi vere ŝanĝis mian vivon’ (it really changed my life). That’s the kind of comment that makes any author purr.

In connection with my discussion of text messaging and its possible reflection of the writer’s accent (blog, 13 March), my former student Georgina Foss writes:

This all strikes me as pretty sensible. Probably I built an unwarranted mass of inference on the basis of insufficient evidence.

However, Michael Ashby mentioned to me today that there are forensic linguists who use analysis of txting style as evidence of speaker identity.

And in India and Pakistan, where /v/ and /w/ are not generally distinguished, they use the letter v in text messaging to represent ‘we’. R V goin 2 do dat, 2?

txtin

There are plenty of words in English that seem to change their stress depending on the phonetic context. Typical examples are afternoon, unknown, sixteen. We say the 'late after'noon but an 'afternoon 'nap, 'quite un'known but an 'unknown as'sailant, 'just six'teen but 'sixteen 'people.

The usual explanation of this is that the words in question are lexically double-stressed. Dictionaries show them with a secondary stress on the early syllable, a primary stress on the later one, thus for example /ˌɑːftəˈnuːn/ or àfternóon.

I think that really the two stresses are of equal lexical status. The supposed difference between secondary and primary merely reflects the fact that when we say one of these words aloud, in isolation, the intonation nucleus necessarily goes on the last lexical stress, making it more prominent than the first.

The alternation goes by various names, including ‘stress shift’ and ‘iambic reversal’, but I call the general principle involved the rule of three. This means that when there are three successive potential accents (= syllables that could be realized with pitch prominence plus a rhythmic beat), the middle one can be, and often is, downgraded, losing its pitch prominence and possibly its rhythmic beat too.

Thus a 'nice 'old 'dog becomes a 'nice old 'dog, and 'very 'well de'signed becomes 'very well de'signed. The 'B'B'C becomes the 'BB'C, and our 'after'noon 'nap becomes an 'afternoon 'nap. Likewise an 'un(')known as'sailant, 'six(')teen 'people.

Anyhow, the point of all this is that when I was in Italy last week I got caught out through applying the same principle, wrongly, to Italian. My room number in the hotel was 202, which in English is 'two 'hundred and 'two, which by the rule of three becomes 'two hundred and 'two. In Italian it’s duecento due, which I discovered does not become *'duecento 'due. It has to be due'cento 'due. That’s because (most) Italian words can have only a single lexical stress. So ‘two hundred’ is due'cento, not 'due'cento.

The consequence is that English people sometimes put accents in the wrong place in Italian, as I did; and conversely Italians find it difficult to apply the rule of three to English double-stressed words.

202

In his recent email, David Deterding continues “[...] I wonder if it isn’t true that all vowels have a indeterminate, semi-reduced version in pre-vocalic environments. Now, LPD uses /i/ for the first syllable of create, which has always troubled me because it is not strictly a phoneme of English and I always believe that dictionaries should show phonemes (though of course I acknowledge that it is phonetically accurate). I further note that you are proposing to adopt this intermediate /i/ vowel for the first syllable of predict and becalm (blog, 29 January). But if other vowels [...] also have weak forms, can this non-phonemic treatment really be justified?

“To be truly consistent, if /i/ is adopted as a neutralisation of /iː/ and /ɪ/ in some environments, we should really find an intermediate symbol between /t/ and /d/ for the plosive in words such as stay and storm.”

David has a point here. Behind the use of /i/ in words such as glorious, and at the end of words like happy, lie two main considerations. One is saving space. If I pronounce /ˈhæpɪ/ but the great majority of my students say /ˈhæpiː/ — i.e. like Jones and Gimson I identify the final vowel with that of kit, they identify it with that of fleece — then we save space by using a special symbol, /i/, distinct from both, rather than by transcribing each such word twice (and there are a very large number of them).

But the other reason, the one to which David alludes, is a more sophisticated one. English arguably distinguishes two vowel systems, strong and weak. Weakening means switching from the strong system to the weak, making a strong vowel weak. Thus [ə] is the weak counterpart of strong [æ, ɒ, ʌ] (and various other vowels), as we see in the strong and weak forms of at, of, us. In exactly the same way, [i] and [u] may be seen as the weak counterpart of strong [iː, uː], as seen in me and prevocalic you, to. Because the weak-vowel system is much smaller than the strong-vowel system, in these positions we have a neutralization (in Trubetzkoy’s terminology, an Aufhebung, ‘annulment’) of some of the phonemic oppositions present in the strong-vowel system.

However, as David points out, these are not the only neutralizations we find in English. The opposition between /t/ and /d/, exemplified in tamp vs. damp, is neutralized after tautosyllabic /s/, as in stamp. So logically we might introduce a new symbol, say /T/, to show it, and instead of /stæmp/ write /sTæmp/. What applies to the alveolar plosives also applies to the labials, as in pin - bin - spin, and to the velars, as in core - gore - score.

As a further example, within the strong-vowel system, I could add the neutralization of /iː/ (bee) vs. /ɪə/ (beer) in the environment _rV, as in the first syllable of serious.

But the practical needs of EFL learners inhibit us from going any further down this path. Even the happY vowel is puzzling enough for many of them.

Following yesterday’s discussion, here’s Masaki Taniguchi:

“The glides in j and w are opening (gliding from closer to opener position), whereas the post-central elements of such English diphthongs as aɪ and aʊ are closing (gliding from opener to closer).

“Can we use the same symbol for both an opening glide and a closing glide?

“I think the essence of j and w is their short duration (quickness) and opening glide, which

distinguishes them from vowels. The post-central elements of the above diphthongs are not quick and not opening.”

He wrote a short paper describing an experiment on this:

Masaki Taniguchi (1986), ‘On the use of j or (y) and w for the post-central elements of English long vowels and diphthongs’,

Bulletin of the Phonetic Society of Japan.

However, what we find in experimental phonetics doesn’t necessarily determine what phonological analysis we adopt. If the opening and closing glides are in complementary distribution, we are free (if we see fit) to regard them as allophones of the same phoneme. Are they in fact in complementary distribution? It depends on whether we recognize syllable boundaries as a conditioning environment. We must be able to distinguish the beginning of RP oasis from away. If both are analysed as having /əwej/ we might be in trouble with David Deterding’s analysis. And that’s one of the reasons I abandoned the bipartite analysis myself.

David Deterding writes from Singapore “I would like to offer a slightly different perspective on the choice of /oʊ/ or /ow/ for GOAT (blog, 9 March). It seems to me that /ow/ makes better sense in American English than RP British English, and the reason for this is rhoticity.

“Let me explain. RP has /ɪə/, which simply has to be represented as a diphthong. In contrast, AmE does not have centering diphthongs because NEAR is /ɪr/ (or maybe /ir/), so all the vowels of American English can easily be represented as a pure vowel followed by a glide. In many ways, won is just now backwards, so there is an argument that both should be shown as a nasal + vowel + glide (or the other way round). And this is why so many American dictionaries use the glide notation while British dictionaries do not.

“I have written it up in a bit more detail here.”

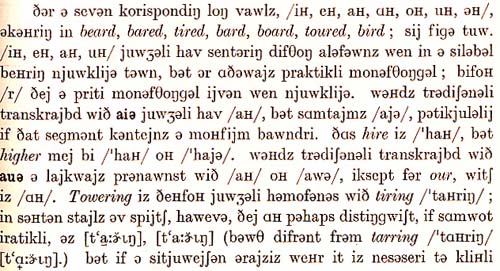

Something that David perhaps doesn’t know is that my first published article, in the Maître Phonétique back in 1962, describing my own idiolect, analysed all long vowels and diphthongs as vowel plus glide. (But since then I have changed my mind, or at least changed my practice.) Here’s a fragment.

|

Archived from previous months:

- 1-15 March 2007

- 15-28 February 2007

- 1-14 February 2007

- December 2006 - January 2007

- 16-30 November 2006

- 1-15 November 2006

- 16-31 October 2006

- 1-15 October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

my home page